Not that anybody gives a fuck anyway

But everybody talkin’ shit probably sucks anyway

Y’all don’t even know how I feel

I don’t even know how I deal

Today I really hate everybody

And that’s just me bein’ real, yeah

— “Anxiety” by Megan Thee Stallion [from Traumazine, 2022]

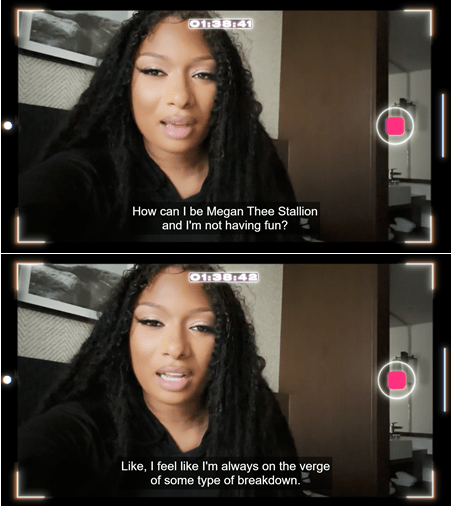

Megan Thee Stallion: In Her Words (2024)’s opening sequence shows viewers at what I would argue is ‘curated vulnerability.’ The rapper records herself in selfie mode as manager Farris follows, a brief laugh follows her declaration that she is tired from Farris “dragging her all around the world.” The sequence ends with a shot of a hand turning the recording feature off, presumably Megan’s hands based on the manicure. While the opening clip shows a bare face Megan, the following sequence opens with Megan sitting in her hotel room alone with a full face of glam makeup; she excuses herself to the unseen audience that she looks like “poop right now” because she simply never went to sleep. The recording is a self-declared admission of the rapper’s need to take a break.

Initially, it isn’t an intense assertion. Rather, Megan coolly shares that is going to cancel her shows; immediately, with an emphasized tut, she clarifies these as ‘obligations.’ Megan intermittently glances away from the camera as she acknowledges her breaking point with clear sincerity; performing and related public matters have not simply exhausted the rapper, but they no longer retain a spark of fun for her. There is a brief pause before Megan references herself in the third person. Acknowledging the relationship that has become attached to her public persona and liveliness, she presents a query to the viewer. How can she simultaneously be Megan Thee Stallion and unhappy with the overtness of this figuration?

Megan Thee Stallion glances away from the camera as she continues her concession. As she looks off into the distance, the rapper reveals that she is “always on the verge of some type of breakdown.” In the shot, Megan returns to a direct confrontation with the camera when she says breakdown. Her gaze is both indiscernible and withdrawn; the viewer might recognize a forlorn essence registering on Megan’s face, but fail to perceive the rapper’s conscious mediation of her testimony.

The subsequent confessional monologue on Megan Thee Stallion’s part functions twofold. One, it becomes the viewer’s interfused reception to the rapper. As a self-documented revelation for an audience, Megan Thee Stallion is inviting viewers to perceive the multitudinous slivers that make up her being. Coupled with the bounce in her exhausted state as she exits the plane with her manager and dog, her restlessness is a result of her bursting schedule. It is not simply a matter of indulging a parasocial intimacy with viewers, but to reveal the internalization of a careful construction to the public. Two, this mediation effectively muddies the boundaries between transparency and private experience. Digging deeper, this moment proposes viewers to think about the boundaries of identity: where does Megan Thee Stallion end? And where do viewers seriously consider the constraints of mediated authenticity? Perhaps most importantly, when and how do we offer humanity to Megan Pete amidst the inscrutability of the terrain of ‘the public?’1

Opening the second part of this review with this example was deliberate.

In the first part, I briefly discussed how marginalized and racialized women have to navigate the destructive expressions of contemporary celebrity gossip culture. My claim was that Megan Thee Stallion (as a Black woman, but also a phenomenon which marginalized/racialized women are often bound by) demonstrates how the ‘echoes’ of responsibility to protect Black men – and by extension, other racialized men to women and/or femme-identifying individuals – can be a moral plight. Consequently, this ethical dilemma places excessive burden upon women to become protectors of men and masculine-adjacent individuals in a world that disproportionately criminalizes and subjects them to harmful generalizations.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s political intersectionality is perhaps the most compatible with this experience: women of color must confront the painstaking realities of their splintered identities. In Mapping the Margins…Women of Color (1991), Crenshaw observed that there is a “need,” an urgent demand placed upon women of color, to confront the actualities of opposing groups that they belong to.2 The consequence of this disempowerment, as Crenshaw argues, is that women of color are forced to embrace the material stakes of one over the other – to choose one betrays the other. Presumably, Megan Thee Stallion felt an internal obligation to choose between these betrayals. By initially presenting her injury from broken glass, Megan shielded Tory from public scrutiny and societal denunciation. However, her misrepresentation came at the cost of her own protection – a dangerous continuation of Black women’s instrumental role as sufferers for the ‘good’ of Black liberation from the survival of harmful generalizations and attitudes.

It’s quite clear Ditum’s stance in Toxic is that celebrity gossip culture was not simply toxic, but that it was destructive on numerous levels. From the image of “the celebrity” to the public who consumed these quasi-popular icons, 2000s celebrity was the spectacle of surveillance culture insidiously wrapped in garish headlines that stoked our willingness to negotiate with a celebrity’s humanity for selfish pleasure. However, the extent of Ditum’s probing stops incredibly short of the real material consequences in how Black and other marginalized/racialized women were perceived in late 90s and early 2000s popular culture. Whether a deliberate omission to reach a broader audience, an oversight to these grim and harmful realities faced by Black and marginalized/racialized women under the scopic lens of continued white supremacist sensibility, or rather a lack of knowledge and depth to the responsibility to engage with these differences, Toxic revealed its limitations in Ditum’s examination on Janet Jackson.

Whatever the actual reasons for Ditum’s inadequate wrestling with these differences may be, the chapters on Aaliyah and Janet seem troublesome at best and malicious at worst. As a scholar examining this text, I cannot dismiss this as mere oversight on Ditum’s part. Rather, her analysis is indicative of how white feminist analysis – however well-intentioned in examining the consequences of patriarchal surveillance culture – reproduces those very exclusions it claims to challenge. Consequently, her analysis is not simply reductive in claiming these as universalized experiences, but becomes increasingly harmful by ignoring how these conditions have been and continue to be shaped by racial and ethnic differences. Here is where the genuine cracks begin to manifest, building toward the analytical failures that will ultimately define Ditum’s work.

If Ditum’s reduction of Aaliyah to R. Kelly’s orbit revealed her inability to engage meaningfully with Black women’s agency, her treatment of Janet Jackson exposes how this theoretical gap becomes politically dangerous. Broadly, the Janet chapter felt underwhelming and suffered from the same disjointedness as the others. However, this was the section where we see how the absence of critical Black feminist frameworks allow harmful narratives to go unchallenged. It’s intriguing how Janet’s chapter flirts with US American cultural and political sensibilities and threading their contours through Janet, yet seems to neglect the core ideological issue of the acceptability of a panoptic culture that vilified those who tested the boundaries toward quasi-‘liberation.’

As mentioned prior, I recognize that it is impossible to include numerous Black feminist scholars in such a short publication. There is no possible way to integrate the full genealogy of critical Black scholarship without purging crucial literature that would be indispensable to reading through Janet Jackson’s career and the role the 2004 Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show3 played in her career. At this point, any critical feminist theory that substantiates the role that race plays and how it is leveraged in our society would have been advantageous to consider advancing her argument about the unfair and cruel treatment of women celebrities in the early 2000s.

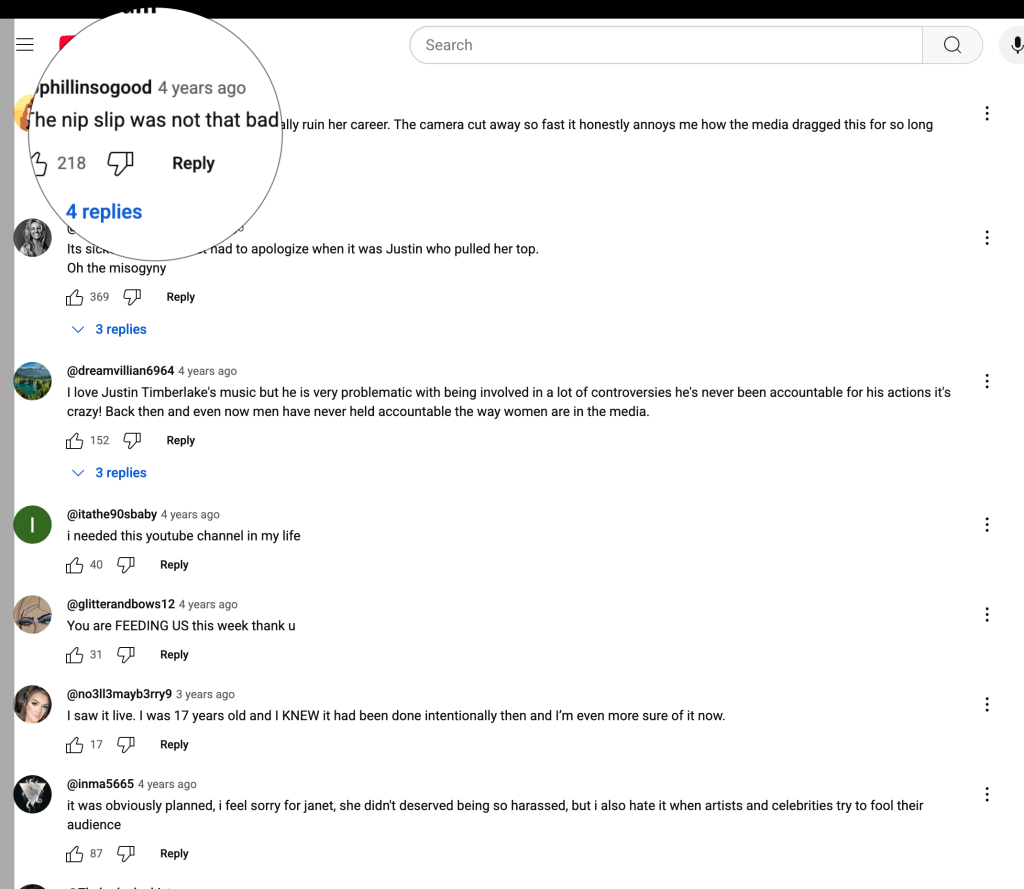

Moments: Janet Jackson’s Superbowl Nip Slip (Nipplegate)” (2021)

For example, Samantha Pinto’s work would have been productive here.

In Infamous Bodies: Early Black Women’s Celebrity and the Afterlives of Rights (2020), Pinto argues that eighteenth and nineteenth century Black women celebrity figures’ public appearances navigate a complex relationship between agency and precarity, and their “infamous” presences produced understanding for modern concepts like rights, personhood, and political subjectivity. Therefore, Black women celebrities specifically offer to us a robust framework for seeing a relationship between fame and politics – and their mediation with the public. In the conclusion, Pinto finishes with the inherent political act of Black women’s ‘publicness’ and how this shapes our awareness of social and political possibilities for contemporary Black women public figures. She states, “The cultural but also political labor of mainstream black women celebrities – from Beyoncé to Oprah to Michelle Obama to Meghan Markle – pressures one anew to rethink the split between culture and politics, and which black women are narrated as serious political subjects while others remain suspect. Infamous Bodies, even as it pivots toward the seeming individualism of celebrity, argues that the act of making, and making public, can be more radically formative for broader visions of political economy and possibility.”4 Pinto pressures us to reimagine this split that has occurred in who we imagine as ‘serious political subjects’ versus those who are easily dismissed for their attachment to popular culture and/or entertainment avenues. This is why we offer legitimacy to the political weight of Michelle Obama– though I remember internet discourse during her tenure was downright malicious – but remain critical of any outwardly ‘subversive’ politics by Beyoncé, who is often ‘just’ an entertainer.

Although Jackson slips into the standard celebrity platitudes about “moving on,” she also has strong if guarded views on the reaction. She says the furor “is hypocritical, with everything you see on TV. There are more important things to focus on than a woman’s body part, which is a beautiful thing. There’s war, famine, homelessness, AIDS.”

The fact that it happened in an election year “did have a great deal to do with it. They needed something to focus on instead of the war, and I was the perfect vehicle for that.”

Jackson won’t blame race for the fact that she has been pilloried while Timberlake has not, but others are less cautious about doing so. “Race had a lot to do with it,” observes Jimmy Jam. “Listen, race always has something to do with it. I don’t think that mid-America is used to seeing a black boob. Maybe that was part of the outrage.”

— Rob Tannenbaum, “America’s Most Wanted” in Blender, June/July 2004 via Wayback Machine

The dilemma with “making public” – as the case is with Meghan, Duchess of Sussex – placed Janet into a cultural moment that immediately became intensely political. This chapter is where we should have felt the strongest overlap between culture, society, and politics, and it would have been compelling to read Ditum’s questioning as to how Janet Jackson became a foil that threatened US American ‘traditional’ beliefs – and the consequence of how her infamy caused her to experience social and cultural rightlessness. The halftime show spectacle had two effects. One, Jackson’s ‘making public’ transformed her from the possibilities of a complex, Black woman performer into a site of moral panic. The material repercussions of this incident left Jackson without rights. Two, her rightlessness makes it clear that Black women’s bodies are subjected to different standards of accountability and punishment; in Jackson the Black female body was a fleshy transgression and required public scorn and punishment to appropriately fit the aftermath of her wardrobe malfunction.

appeal? The Simpsons ft. Powell

For example, Ditum’s inclusion of FCC Chairman Powell’s invoking of “Our nation’s children, parents and citizens deserve better” (112) explicitly ties back to my earlier comment from Edelman, and we can also connect this to Pinto’s broad argument regarding modern conceptions of rights, their connection with sexuality, morality, and femininity, and Black women’s bodies as ‘public’ sites for such discourse. Revisiting Edelman, Powell’s invocation turns us back to the deliberate weaponization of ‘the Child’ as a rhetorical device to punish a Black woman’s sexuality. Edelman’s argument directs us to witness how reproductive futurity concentrates upon an impossible future because all political imperatives are focused on preserving the mythical ‘Child.’ The true material consequences of directing our energy toward this ‘Child’ is that continuing to shape policies and actions onto preserving this hypothetical figure reduces the possibilities of freedom or liberation for real people.

Ditum only superficially explores how the ‘protection of children’ narrative served multiple purposes. One, it allowed America to perform moral outrage while simultaneously consuming and profiting from the controversy – the evolving digital world offered people to be one click away to send a complaint and birthed YouTube to crystallize the fiasco. Two, it provided cover for racist double standards in how Janet was treated compared to Justin (this felt like an afterthought, more on that in a bit). Three, it revealed the hypocrisy of a culture that commodifies female sexuality until the moment it appears to escape controlled boundaries – and how Janet was desexed as a punishment following the infamously anointed ‘Nipplegate.’ The argument is that the wardrobe malfunction became a national crisis not because Americans were genuinely concerned about children seeing a breast for less than a second, but because Janet – a successful Black woman who had embraced her sexuality on her own terms – momentarily disrupted the fantasy that America’s repressive sexual attitudes were natural and universal. (Another interesting contradiction that is a feature of the 2000s.)

Ditum gives the impression of scratching the surface of what I alluded to earlier (and something which she is guilty of): that politics – conservative and progressive alike – relying on the abstract notion of futurity to sacrifice marginalized peoples for its continuation; in their continued abandonment, ‘progress’ is perpetually on the horizon, a disembodied non-possibility that is worth the cost. She does a decent job at examining the interwoven nature of society and politics that affected Jackson, post-Super Bowl performance (and mentioning that Powell’s crusade was a failure, karmic relief), but she leaves plenty to be explored around the relevant issue of a panoptic US American society that disguises the chattel of women (especially an older Black woman who had immense crossover success and embraced her sexuality through and by her own terms) as ‘lay of the land.’

Considering Powell’s words more carefully reveals the deeper racial dynamics at work. We can see how Jackson’s ‘spectacle’ – whether we believe it to be artifice or not – destabilizes and jeopardizes the stability of US American society through the fabric of the family to the child and into citizenry. As an intentional maneuver, the halftime show wardrobe “malfunction” exploits the tenuousness of future generations in a lewd display. If it was unplanned, Jackson’s mishap had the unforeseen consequences of surprising the American public with a revelation of sexuality that it was unprepared for (and undeserving of).

What makes Powell’s condemnation particularly insidious is how it positions Jackson’s Black female body as inherently threatening to American futurity. Whether the exposure was planned or accidental becomes irrelevant – Jackson’s Blackness all but ensures she cannot escape culpability. If intentional, she is a debaucher of American values; if accidental, she represents uncontrollable sexuality that must be regulated to protect an already delicate social order. The lose/lose positioning reveals how Black women’s bodies are always and readily seen as threats to the mythical Child’s future.

The racial dynamics become even more complex when we consider that Powell himself is a Black man wielding state power to discipline Black female sexuality. His invocation of ‘our nation’s children’ performs a kind of racial distancing, positioning himself as protector of (implicitly white) American futurity against the threat posed by Jackson’s transgressive Black female body. There is plenty of post-colonial literature that would apply to Powell’s actions (and the deliberate binary positioning that can impact marginalized/racialized individuals): scholarship on the psychology of colonization and its effects has a robust lineage in the works of Fanon, Césaire, Memmi, and Freire. Even a brief engagement with these frameworks would have transformed the stakes of Ditum’s reading of Powell and Jackson – and how they became unwilling (and unsuspecting) pawns in a larger issue. Yet returning to the unique dynamic between Powell and Jackson, this interaction exposes how systems of power can and often do co-opt marginalized/racialized individuals to police other marginalized/racialized bodies. Consequently, this collusion creates a facade of racial neutrality while simultaneously reinforcing white supremacist logics of surveillance and control.

What’s particularly revealing is that Ditum seems unaware of how deep these influences run, even in her own writing. For example, she fails again to identify Justin’s complicity in the tabloid humiliation of Janet and Britney, particularly how Justin manipulated these incidents as capital for his own solo expansion. Ditum extends sympathy to Justin in Britney’s chapter where she initially traces his boyband origins – and the predator who wielded supreme authority during those years – and fully fleshes it out near the concluding remarks in Janet’s chapter. Ditum highlights for the reader that “Timberlake – a former boy bander at the precarious beginning of his career in 2004, only a few years free from the predations of ‘NSync manager Lou Perlman and highly reliant on the goodwill of the media – was not particularly powerful in entertainment industry terms.” (128) Timberlake is a passive tool, and earns sympathy from Ditum; having endured Perlman’s maneuvering, he is both inexperienced and susceptible to mass media’s whims. To a point, yes, Timberlake comes across as the emerging somebody that is cognizant of the fickle nature to much more powerful media despots that could devastate his possible longevity.

However, it seems that Ditum forgot that she’d marked Justin as accountable, too.

Specifically, near the first pages of Janet’s chapter, Ditum mentions that Justin gave the first comment to the media on the incident as a deliberate production. “‘Hey man,’ he blithely said to Access Hollywood in a post-show interview. ‘We love giving ya’ll something to talk about.” (111) Whether Justin was a participant in the spectacle or not is not necessarily the stakes that we should be raising; rather, it’s Ditum’s failure to recognize and advance Justin’s blithe proposal of direct responsibility in the act. If we invest in a charitable reading to Timberlake’s decisions, then it’s crucial to acknowledge the Super Bowl halftime show incident’s contradictions. For one, Justin’s ‘participation’ as a negligible player amidst the media circus reveals that his exclusion from the media’s criticism of the incident illustrates the media’s insatiable appetite, a carnivorous ephemeral organism that subsists on women’s very public, effacing, and humiliating punishment. The effect here is that we should recognize the patterns of how particular individuals and their sense of humanity can be stripped from them in order to shock the system for their own profit. An additional inscription of Justin’s invocation is that – on some level – he mobilized the scandal’s essence for both himself and Janet. This just further proved to me that Justin was always a horrific, entitled, bratty, and self-absorbed drama king who finally reaped what he had sown – the Britney chapter briefly alluded to it and probably should have been much less sympathetic to him (because why are we focusing on giving nuance to men bit parts in a publication whose premise is partly about the rehabilitation of women celebrities during the 2000s?).

If Ditum’s treatment of Justin does not reveal her analytical inconsistency, it manifests most poignantly in the Kim chapter. If there is any chapter which reveals her abject helplessness in grappling with her own on-the-perpetual horizon argument, it is broadcast loudly in this one. Frankly, this chapter was the section where I was acutely aware of Ditum’s limitations – and the analysis where I found myself ready to the toss the book in the trash because she was wholly incapable of wielding the burden to pull the dilemma of Kim “‘Get your fucking ass up and work. It seems like nobody wants to work these days.’” K apart.

Not realizing how long this review has become, I have opted to turn this into a trilogy (cue Randy’s “The Rules of Trilogy” dialogue & Dewey’s breathy ‘Trilogy?’ response to Randy’s video self). In the final part of this review, I’ll do my best to dissect Ditum’s analytical failures and how they peak in her treatment of Kim Kardashian (because who isn’t tired of hearing about America’s First Family of Social Media after two decades – and counting?). Kardashian is probably the most apt figure who embodies the transformation of surveillance culture that Ditum fundamentally misunderstands. It is in her exploration of Kim that Ditum’s work moves beyond politically dangerous: a willful blindness to celebrity and gossip culture’s complexities that masks the deeply embedded insidiousness of relinquishing ‘control’ to intangible but pervasive hegemonic structures.

Notes

- Currently, there are approximately 3? 4? pieces I have in the works about Megan Thee Stallion — I find her undeniably fascinating. But I also find she reveals immensely terrible conditions that bind women, but particularly Black women. I’m specifically interested in the double bind that Megan Thee Stallion is in: when directly addressing her trauma and the reclamation of her power through music and persona reveal how she can be painted as leveraging victimhood while simultaneously being inauthentic because of how she chooses to address these troubles.

Black women deserve better from all of us. I’ll always do my part to amplify their voices and concerns when and however I can. ↩︎ - Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (Jul. 1991): 1252. ↩︎

- This incident is identified through other terms and I choose not to refer to it by these designations unless I am quoting another author/writer. If they should appear in my own writing, the aim is to be critical and apprehensive of their application. ↩︎

- Samantha Pinto, Infamous Bodies: Early Black Women’s Celebrity and the Afterlives of Rights (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 205. ↩︎

Leave a comment