Disclaimer: This is part one of a two-part review series. Part two: TBD.

As I mentioned in my previous post, I am a Millennial byproduct of celebrity gossip and tabloid culture. This formative influence has become one of many personal interests I have turned into academic pursuits (insert the iconic Tiffany’s ‘Beyoncé? BEYONCÉ??’ meme here) — a pattern that reflects my inability (or unwillingness) to separate personal fascination from scholarly inquiry. Reading was one of my favorite childhood pastimes,1 and it’s never stopped being a delight in my world (except when I’m forced to reading something against my will). Last year, I began contemplating undergraduate courses that I wish existed, with my first creation being a brief survey of reality television during the 90s and early 2000s.2

I stumbled on Ditum’s Toxic: Women, Fame, and the Tabloid 2000s in Barnes & Noble. Standing in the store aisle, there was a brief moment where I relived the pageantry of the early 2000s — from the whirl of daily tabloid magazines to the dresses-over-jeans fashion to the influx of blogging and personal websites (RIP GeoCities). I felt like a certified Old-Timer™ trying to explain to my husband how ‘cool’ it was to remember the decadence and kitschy qualities that permeated that era.3

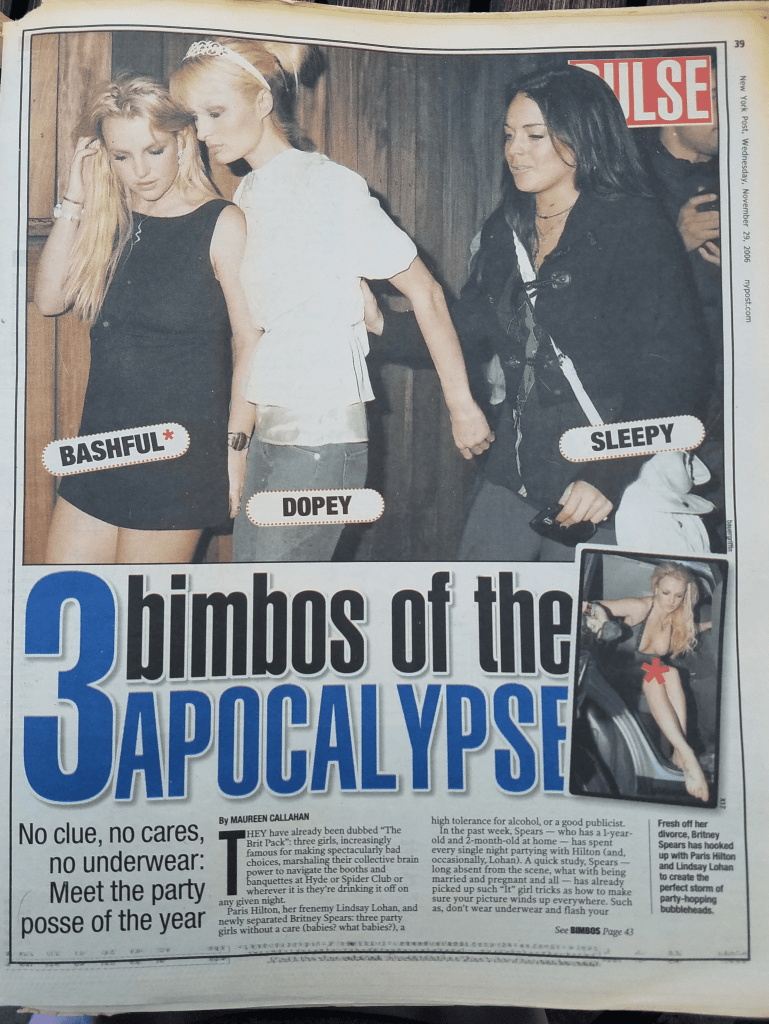

Fig. 2. “The Three Bimbos of Apocalypse,” scan of New York Post’s November 29, 2006 tabloid. Courtesy of reddit user Preesi, posted on January 3, 2023. (source)

I don’t really write reviews. I always have plenty of opinions, thoughts, musings, but they never seem interesting enough to broadcast: an ironic development for a Y2K-offspring-turned-Millennial heir. But it’s a new year, and I find that now is an immensely appropriate time to begin sharing what I have to say, especially as our culture teeters between digital fanaticism and moral suspiciousness. McLean’s ‘Digital Anthropocene’ marks an epoch where digital technologies are inextricably connected with human understanding and experience, which impacts the ‘natural’ world and produces new power dynamics and mediated relationships between humans and the non-human world.4

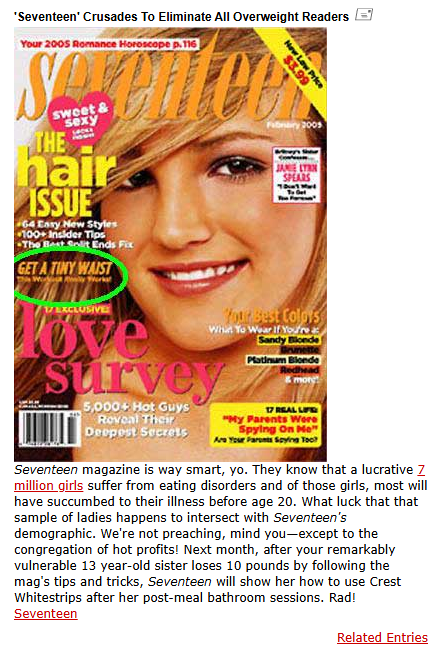

Much like how the Digital Anthropocene transforms power relations between humans and the non-human world, social media — and the increasing digitization and platforming of celebrity gossip culture — has shifted the traditional links between celebrities, media outlets, and mass audiences and consumers. This means that our attachment to celebrity gossip might have been superficially disrupted, but the underlying currents of surveillance and fascination continue to tether us to its existence. I harbored some optimism about Toxic, particularly because I was so grateful to discover a book that seemed marketed to a former 2000s youth girlie who was trying to break free of the rigid warmth I associate with academic texts. It was incendiary, and I was excited to immediately dive into the book: who didn’t want to relive the enchantment of 2000s celebrity snark and the infectiousness of tabloid debauchery?

In particular, I was looking for a book that would grapple with the delicate balance between self-awareness and profound criticism of the spectacle of the early 2000s. It was also an opportunity for me to momentarily break up with academic publications for something that felt like a good compromise: a nonfiction piece that would challenge our participation in those cultural temptations of offhand cruelty. Unfortunately, this is where Ditum’s analysis falls short. She interprets the ‘Upskirt Decade’ as a past relic upon which we should reflect, revealing the unnecessarily harsh and spiteful cult we developed toward women celebrity figures. Her conclusion is optimistic: the cruelty of our gossip past has left us more empathetic in treating celebrities as public keepsakes who do not function as moralizing vessels. In reality, I disagree. Surveillance culture and the fascination that drove Ditum’s ‘Upskirt Decade’ continues unabated, just in more sophisticated and widely dispersed transnational forms. We only have to look at the continued proliferation of gossip subs, communities, TikTok gossip influencers, and algorithmic communication models to illustrate that it’s mutated into a contemporary, standardized form.

The ‘Upskirt Decade’ hasn’t disappeared at all — it’s evolved and intensified. We have replaced chaotic paparazzi runs with parasocial relationships, tabloid headlines with trending hashtags, and public shaming with ‘cancel culture.’5 Our collective impulse to scrutinize, judge, and penalize hasn’t diminished; it’s merely adopted a veneer of moral righteousness that masks the same voyeuristic hunger that fueled the tabloids of the 2000s. I’m guilty of it (my husband calls me a ‘connoisseur of gossip’). What Ditum missed, and I think a few other reviewers caught this, is that our culture hasn’t necessarily changed; we’ve just used algorithms and social media platforms to camouflage the devouring of women celebrities for profit (and for clicks, likes, subscriptions, and presence).

And if women are for sale, thrown to the court of public opinion on a whim, then other marginalized people — particularly Black women — have no refuge. We see this in how Megan Thee Stallion, Jada Pinkett Smith, Simone Biles, and Naomi Osaka face intensified scrutiny that combines the worst aspects of misogynoir, all while platforms claim to promote diversity and inclusion.6 Becky G has dealt with criticism from within the Mexican American and Latine/x/a/o community regarding her cultural authenticity and language skills, while simultaneously receiving sympathy amidst cheating allegations. Jameela Jamil is routinely perceived as a communal nuisance for her numerous avenues of advocacy. The intersection of race, gender, and celebrity reveals that while the mechanisms of surveillance have become more sophisticated, the hierarchies they enforce remain stubbornly familiar. This is the continuity that Ditum fails to fully acknowledge: the tabloid culture she examines hasn’t ended; it has simply found new, equally destructive expressions. And we are complicit.

Some brief remarks before I continue: I want to acknowledge my biases with both the author and publication itself. It’s also worth mentioning that I read this book at a deeper level than a casual reader, particularly to gain insight for the course I am developing on the spectacle economy, tabloid aesthetics, and surveillance culture.

Those who are familiar with me are aware of my preferred reading material. First, I have an affinity for academic-oriented publications, so reading nonfiction texts that don’t have an extensive Chicago-Turabian notes or Bibliography section can be a little difficult for me. This is for two reasons: one, I am a scholar, so ‘following the end/footnote’ is a way for me to grasp the sources that inform the publication; two, I often find other interesting texts that are related/adjacent to the initial publication, so it’s a personal win for me. I struggle with non-academic nonfiction books probably for a similar reason that others struggle with the opposite: I have trained myself to be accustomed to a particular writing style, so the more casual/informal tone in these publications often makes the content’s stakes feel lower (this is just my observation!).

Specifically, I’ve come to value not just the attributive function of end/footnotes, but how they create a secondary layer of discourse — where critical evaluation, voice, and practice intertwine. End & footnotes don’t just operate as a space for proper attribution and citation practices; rather, they are a part of a writing convention that creates scholarly conversational spaces (we talk to ourselves but talk to other scholars here too!). Footnotes become a contextualizing avenue for argumentation, limitations, counternarratives and distinct counterpoints. They are where we showcase our intellectual labor, the work literally behind the work, and reveal the intellectual transparency of how we are evaluating evidence — our assessments, assumptions, critiques, interpretations, revelations. Whether these are notes at the end of each page or act as the document’s concluding labor, it’s a space where we recognize these complexities — I call it my ‘epistemological humility.’ It’s a space where I don’t deviate from my work’s purpose in text, but I offer my contributions, assessments, or synthesize how and why I have substantiated an idea, concept, or claim. In non-academic writing, evaluative claims often appear without this visible scaffolding of intellectual deliberation, which can make the analysis feel less rigorous or self-aware to me, even when the insights themselves might be valuable.

Two, Two, I am acutely aware that the author has participated in platforming transphobic beliefs on a national scale. Jacob Breslow’s research shows how media personalities and pundits – including writers like Ditum – often use what he calls a ‘third conditional’ argument – the “if I had grown up today, I would have been persuaded to transition” narrative.7 This rhetorical approach creates a hypothetical threat that never actually happened to the speaker but is presented as something that would inevitably happen to vulnerable children today.

(Side note: This fixation on ‘the child’ connects directly to Lee Edelman’s influential work No Future, where he identifies ‘the Child’ as the central figure in what he calls reproductive futurism – a political framework that positions the innocent child as requiring protection against supposed threats to their future. Edelman argues that queer identities are routinely cast as dangers to this idealized Child, positioning them as ‘antisocial’ and ‘future-negating.’ When anti-trans advocates deploy hypothetical scenarios about ‘children being persuaded to transition,’ they’re tapping into this exact rhetorical pattern: creating a false binary between protecting children and affirming trans identities. This isn’t just casual transphobia – it’s part of a systematic deployment of ‘the Child’ as a political weapon against any identities deemed nonnormative.)

From a personal perspective, I would rate this book a 0/5 because the proliferation of transphobic discourse is never acceptable in my view. What troubles me most is how these seemingly offhand remarks create channels for supposedly ‘innocuous’ commentary that, when accumulated across media and literature, normalize harmful perspectives. These small instances aren’t isolated — they contribute to a broader cultural permission structure that gradually entrenches transphobic attitudes as reasonable or unworthy of challenge. For example, I was particularly unsettled by Ditum’s casual deadnaming of two trans individuals. This practice is unnecessary — established writing conventions already exist to respectfully discuss trans people’s work and history, as we routinely demonstrate in academia (J. Halberstam being a prime example). The author’s choice to ignore these conventions reflects a deliberate editorial decision rather than a lack of alternatives.

Unfortunately, I purchased this book without researching the author’s stance on trans issues; had I known about her pattern of insensitivity, I would have made a different choice. While I firmly believe that issues affecting cisgender women deserve robust discussion and advocacy, this can and should be accomplished without resorting to rhetoric that reinforces the very hierarchical power structures that have historically marginalized women. This viewpoint was discernible in her early chapters on Aaliyah and Janet but became palpable in her Kim analysis — more on that later. The false opposition between women’s rights and trans inclusion ultimately undermines both causes. Ignoring ‘small’ instances accumulates into larger cultural problems because they reproduce harmful patterns when we don’t challenge them — we can always flag issues and uplift others’ meaningful contributions and existences alongside our own.8

Like Ditum, I was a byproduct of 90s/00s culture; I was a chronically online teenager who absorbed celebrity gossip and tabloid lifestyle as a part of my identity (admit it — we all did). I regularly devoured gossip sites like Lainey Gossip, CDAN, ONTD, and Dlisted, alongside daily doses of US Weekly, Star, OK! Magazine. Even now as an academic, celebrity gossip remains my guilty pleasure escape (and when I tell my students this, they breathe a sigh of relief that I am flawed, too). As we move forward, we seriously need to reflect on the reality of our pop culture past: we were a cruel society and terrible participants in the late 90s and early 2000s.

What Ditum’s case studies of ‘devoured’ women miss is a deeper examination of what she called the ‘Upskirt Decade.’ Certainly, she does make it clear that we weren’t just passive consumers of cruel content, but active participants in a toxic ecosystem that delighted in the excesses of celebrity as much as we condemned them for such waste. The true consequences of that early digital Wild West Web weren’t just that individual women suffered (they certainly did; I walked away with self-esteem and body issues that still linger). Rather, it was that this period in pop culture revealed our collective anxieties in a post-9/11 landscape where surveillance culture was normalized, celebrated, and expected. Personal autonomy was something both public figures and everyday citizens had forfeited (whether they knew it or not).

Fig. 5. Paris & Lindsay at the early 2000s celebrity capital, Kitsons in LA. Courtesy of twitter user @2000sthetic, posted December 8, 2021. (source)

The celebrities we built up and tore down weren’t just entertainment – they were convenient avatars onto which we projected our failures of ‘good’ citizenry. While Ditum catalogs the wreckage, she missed the opportunity to examine why we so eagerly participated in this destruction or ask how this has transformed our relationship to social media platforms and digital technologies; this feels particularly significant in the ‘Era of the Influencer.’ This limitation might be ascribed to location: I grew up in the U.S. so my capacity to reflect on the absorption of early 2000s American culture gives me a different perspective than Ditum. But I wish that had been the book I had read.

Ditum briefly alludes to the ‘democratizing’ celebrity condition in her conclusion — how this ‘toxic’ celebrity culture of the early 2000s did become a universal position for everyday people. However, her analysis falls short by presenting this development as a novel condition for all, rather than recognizing how marginalized communities and racialized people, particularly Black women, have long lived under these forms of surveillance and moral judgment. What Ditum frames as a new “baseline condition of modern life” (pg. 241) has been the historical reality for racialized bodies for generations. The 2000s celebrity culture didn’t create this dynamic: it merely expanded and normalized its reach to previously insulated demographics.

This oversight reflects the most significant contradiction in Ditum’s work: her lack of self-reflexivity regarding how Toxic itself participates in the very ecosystem it critiques. The book’s existence — and indeed my analysis of it — demonstrates how our cultural appetite for examining women’s public trauma remains undiminished. We haven’t become more charitable; we’ve simply repackaged our voyeurism under the veneer of cultural criticism and historical reflection. This disguises our continued participation in systems of surveillance while allowing us to distance ourselves from their devastating effects, even as we perpetuate them through our continued consumption and analysis.

The most glaring shortcoming of the text is that the introduction is framing the women as ‘ambivalent’ figures without seriously pressing on the notion that these nine women were not entirely active participants in the capital they provided for the public. Yes, these women altered, shifted, played with, leveraged, and negotiated their status in the media as best as they could with the little possibilities they could within a misogynistic patriarchal society. However, I think this is a simplistic reading to the intense pressure that these women were under — and we should call into question what ‘agency’ Ditum is aiming to address. The spectacle of their entertainment was about the gratification and pleasure of reducing the capacity of ‘autonomy’ in every possible way. I believe had Ditum framed the moral greyness of society at the time in conjunction with how these women responded to the best of their restricted abilities, it would have been more scathing as to how willing we were to destroy these public figures — all women — with delight. And we can be cautious about placing a contemporary lens over this period (who wants to be chastised for these transgressions when everyone was equally complicit and guilty?), but I believe framing some of the contradictory beliefs of society and cultural attitudes at the time would have been much more fascinating. It calls into question mechanisms of control, and how we have adapted them in accordance with the ‘feelings’ that are dominant during a specific time — like the concept of hysteria in the 18th century.

What’s perhaps most disturbing about this evolution is how thoroughly voyeurism has been absorbed into our conception of selfhood. The cultural shift that began to materialize in the ‘Upskirt Decade’ has completed its transformation: surveillance is no longer something externally imposed, but something we have internalized and reframed as self-expression. We don’t just watch others. We anticipate being watched ourselves and craft our identities accordingly. The collective impulse to scrutinize has been repurposed as a tool for personal brand management, making us simultaneously the voyeurs and the observed. This dual positioning wasn’t invented in the 2000s, but it was perfected and democratized then, creating the foundation for our current moment where the boundaries between private experience and public performance have completely collapsed.

Rather than destroying the system, we’ve elevated it into a defining feature of contemporary identity — turning what was once a collective cultural sickness into something resembling personal choice. We curate our lives as spectacles, anticipate criticism before it arrives, and police our own behaviors with the same vigilance once reserved for celebrity missteps. The ‘feelings’ that dominated the 2000s haven’t disappeared. They have been redistributed, internalized, transformed from external cultural forces into the very architecture of how we understand ourselves. Ditum misses this critical evolution, focusing instead on surface-level changes in how we treat celebrities; her conclusion would have been poignant had she pulled apart that examination of this ‘universal’ prerequisite and how thoroughly we’ve absorbed the logic of surveillance into our sense of self. However, mass culture and society seems incapable of reconciling this transformation because they remain fixed on the obvious: how ashamed they are to have been engrossed in what they called ‘trivial.’

So many of the chapters started off strong, with acute interventions that outline the “sensations” for each woman’s 2000s media narrative. Britney’s starts in 2008, leaving her home on a gurney; Paris’ begins with Perez Hilton’s 2005 evolution; Aaliyah’s with her premature and tragic death in 2001; Kim’s with a 2007 KUWTK snippet. However, they stumble to maintain their focus.

The Aaliyah chapter isn’t the only weakness in her analysis (more on that) – it’s perhaps the most frustrating for two reasons. Primarily, it fails to center Aaliyah’s own agency and artistry. This is compounded by Ditum’s broader inability to engage with race beyond surface-level acknowledgments. Given that the target audience is a general reader, I acknowledge the integration of Black feminist scholarship in understanding Aaliyah’s life and career would be challenging. Ditum flounders in this chapter explicitly because she elects not to utilize a robust arsenal of critical Black feminists to dissect the nuances of misogynoir that affected Aaliyah, the Black community in the US, and the popular imaginary on/toward Black community issues. She applies the credit of Aaliyah’s artistry and the spectacle of her legacy to R. Kelly, and it is overwhelming and frustrating to see so much of her life as a ‘tragic’ ougrowth from the inconsistencies of the R&B singer.

For example, Aaliyah’s chapter is approximately 26 pages. The chapters range between 24 to 29 pages; Janet’s chapter is the remarkable 29 pages, followed by Kim’s at 28, and both Aaliyah and Paris’ are 26 pages. 10 However, more than half of the Aaliyah chapter is fixated on chronicling R. Kelly’s career, the intertwining of legal troubles and musical pursuits during the early 2000s, and tangential snippets of the other era’s offenders (Chris Brown & Terry Richardson). When Ditum enlarges the binary problem in the 2000s between victim & abuser, Aaliyah was awkwardly lost in the process. She writes,

“Learning the truth of what happened to Aaliyah during her lifetime had been a grinding process of tracking down documents, and whatever was uncovered was limited in its reach by the constraints of print and broadcast media… you couldn’t know for sure what the charges against Kelly consisted of.” (pg. 94)

Partly, Ditum is acknowledging that excavating Aaliyah’s quasi-ephemeral presence — here briefly and then abruptly gone — calls on us to speculate the possible future of Aaliyah’s life had she lived. To try to reconcile with Aaliyah as both victim and survivor to such scandalous murmurs and frenzied gossip means that we need to examine how the culture of the 90s and early 2000s dealt with the victim vs. abuser problem: to be a victim in this moment could mean nothing more than you were also deliberately perpetuating harm and mistrust, while also terrorizing someone else for that wrongdoing. The optics of this look vastly different now, but this also the culture Aaliyah was entrenched in; on some level, Aaliyah was probably aware that living and participating in this society and culture required her to overcome these violent histories and events because that is simply what is expected of them.

And yes, Ditum does invoke Crenshaw to foreground the precariousness of Black women in this moment. Crenshaw is a fantastic scholar to leverage the impossibilities that emerged during the hostile post-Reagan ‘welfare queen’ American environment and the pressure of responsibility to protect Black men — often which comes at their own expense and well-being (you only have to look at what happened to Megan Thee Stallion to witness those echoes). However, Ditum is either overwhelmed by the broader sociocultural problems she’s unveiled in Aaliyah’s chapter, or she simply doesn’t have the insight to how race shapes celebrity narratives and society’s internalization of these subcultural dynamics.

For example, analyzing Aaliyah’s precarious position as a Black woman provides a sense as to why she was so elusive or ‘impersonal’ (as she later writes in the Amy chapter introduction). She could have benefitted from digging her heels into Crenshaw’s analysis of Black feminism and 2 Live Crew (“Beyond Racism and Misogyny”), hooks’ critical examination of the societal context of gangsta rap (“Sexism and Misogyny: Who Takes the Rap?”), Hill Collins’ work on how Black women navigate these multiple matrices of oppression (Black Feminist Thought), Davis’ acknowledgment of Black women’s positioning between these increasingly political identities (Women, Race, and Class), and Spillers’ revolutionary text exploring the position of Black women within American culture specifically (“Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe”). While these are perhaps could be overwhelming for a casual reader, Ditum fails to wield her material in an appropriate manner, egregiously overlooking how racialization is a lived experience that Black women cannot recoil from.

Ditum’s treatment of Aaliyah reveals the first glaring crack to her analysis, divulging her fundamental limitation in her approach to embodiment and race. For example, where scholars like Amber Jamilla Musser understand flesh as “the site through which knowledge is taken in and produced and then how it becomes externalized and how we organize ourselves,”11 Ditum treats Aaliyah’s body and image as merely a site of victimization rather than a complex locus of knowledge production and resistance — particularly insightful when we acknowledge that Aaliyah was only twenty-two years old when she passed away, navigating the subtleties of her life experiences and desires on a public stage. During the early 2000s, the casual and inherent misogyny that was part of our cultural texture was simply ‘the way it is.’ Downplaying or shifting the conversation away from previous failures on Aaliyah’s part was her capacity to recognize this fragile boundary; it was Aaliyah’s way to reattract audiences and the public to her artistry, but to recenter her voice and choices to cultivate her own identity and persona as she so liked.

In doing so, this aligns with Musser’s argument of “thinking through this knot of modern racialized sexuality really means thinking about the particular way that the flesh has been reorganized.” Aaliyah navigated and renegotiated the organization of her ‘flesh’ (her sense of being, self, the externalized projection that we got to see) within the constraints of the entertainment industry and broader American culture. Ditum does not simply fail to engage with this, she seems to miss this as being fundamental to the continued fascination and admiration for Aaliyah’s legacy. Ditum reduces her to a passive recipient of R. Kelly’s influence and abuse, acknowledging that Aaliyah was caught in these machinations — we simply did not have the ability to watch her, over time, maneuver herself to stardom and away from these past events.

Aaliyah would have been a great candidate in this case study to explore how her carefully cultivated persona represented her own aesthetic response to these constraints — not an ‘impersonal’ and indifferent suppression from the media and its obsession with speculative murmurs. This relates back to Musser’s description of “how people are enmeshed in society” through their bodies. Aaliyah’s ‘impenetrable aloofness,’ her distinctive style, her careful navigation of sexuality constituted a complex negotiation with the racialized and gendered expectations placed upon flesh. Ditum missed this opportunity and simply seemed more invested in exploring Kelly’s monstrousness and using Aaliyah as a necessary contrast to establish the destructive sensuousness of Amy in the succeeding chapter. The absence of this deeper analysis reveals how Ditum’s work, despite a critical position toward tabloid culture, remains trapped within its superficial frameworks. Ditum’s omission of other poignant scholarship leads her to the pitfalls of Musser’s legible “scientific discourse” — a straightforward demographic fact. The problem with this examination is that it is shallow and misguided, and leaves readers underwhelmed. The lived complexity of racial embodiment that requires ‘different types of decoding’ to fully comprehend are complete omissions, signaling to readers that Ditum is merely focused on transforming Aaliyah’s life and legacy into a painstaking blip on celebrity culture radar.

Fig. 8. Aaliyah’s legacy in her own words. Courtesy of MTV News on YouTube. (source)

In my reading, the true tragedy of Aaliyah’s story isn’t just her premature death. It’s how our tabloid culture, and now Ditum’s book, continue to define her primarily through her connection to R. Kelly. We simply cannot allow Aaliyah’s story and her contributions to be standalones; we continue to return to the scrupulousness of those who contrived her prematurely ended career and life. It is important to recognize how this framing denies Aaliyah credit for the ways she worked to establish her own identity and artistic vision, despite how her image and artistry were manufactured for her as a little girl. Certainly, knowing the origins of Aaliyah encourages us to praise her authenticity and meteoric rise; however, her manufacturing seems to encourage us to neglect and omit how much of this was her story. By relying entirely on outsiders’ perspectives and allowing R. Kelly’s violations take precedence in this chapter, Ditum perpetuates this erasure rather than challenging it. For example, we never acknowledge how Aaliyah wanted her legacy to be as an ‘entertainer’ and as a good person. We never get the fullness of how Aaliyah saw herself – cultivating her brand and ‘trained to do it all;’12 we also don’t explore how Aaliyah was juggling the different demands of stardom, the significance of her crossover into other artistic mediums, and how she was grappling with transitioning into adulthood in the then unforgiving and scrutinizing public eye. (I also wasn’t fond of the subtle malalignment to ‘Queen of the Damned,’ which is an homage to 2000s nu metal vibes and doesn’t ask us to take it seriously – Aaliyah was perfect for that role.) We simply end her story with what we already knew: R. Kelly the monster birthed the ‘gone-too-soon’ and briefly candid account of Aaliyah’s life.

This review is much lengthier than I initially anticipated. In order to avoid this becoming a single-setting ~50-minute read, I’ll cover the other case studies in another post — continuing with Janet, then leading into Kim. Feel free to ask questions that I can or should cover (this is the first time I have ever publicized my opinion on a book on a public form!).

Notes

- The Pasadena Central Library remains one of my favorite places on this earth, mostly because we spent so much time here as kids. It was a short bus ride away, and I will never forget the first time my eyes widened when I was told I could check out numerous books for free. A lifelong passion was born in this library, I wish I could have spent more time here during my earliest undergrad years. ↩︎

- Another guilty specialty of mine is contemporary reality TV, especially the 90 Day Fiancé franchise (I frequently tell my husband “Who is against the Queen will die!” and “No creature on Earth, except for my dog, is ever gonna control me.” when I am struggling with research, or our fur babies are being stubborn.) For me, the pleasure in reality TV is seeing the different performances that people utilize to cultivate a sense of identity — and how these are framed or put under pressure by the camera and audiences. But also, it’s fascinating how much people invite the unknown into their world. ↩︎

- A note to my husband, who unwittingly serves as collaborator in much of my research and writing: you get a pass for missing the details of these decades. Our ‘modest’ age gap (which you insist isn’t significant) actually reveals how dramatically different our experiences with popular culture were growing up. The early 2000s hit differently depending on whether you were a teenager or an adult when Paris Hilton and Britney Spears dominated headlines (and where you ingested that content). ↩︎

- Jessica McLean, Changing Digital Geographies: Technologies, Environments and People (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 160. ↩︎

- I won’t digress into this phenomenon. But it stinks, and we should be talking about its inadequacies. ↩︎

- Simone Biles’ treatment is particularly heinous, where everyone abruptly became a life-long gymnastics expert as a means to punish and discredit Biles for stepping back when she felt it was necessary. Something that felt immensely underdeveloped is the different levels of public engagement that are afforded between white and Black women (as well as other racialized women). Black women are held to a different standard in celebrity culture, and it isn’t surprising that Ditum only scratched the surface when acknowledging how this impacted the treatment between the two Black women cases she discussed here (Aaliyah and Janet) and the other women. ↩︎

- Jacob Breslow, “They would have transitioned me: third conditional TERF grammar of trans childhood,” Feminist Theory 23, no. 4 (2022). ↩︎

- Side bar: I am going to take this moment to really dig in here re: Ditum and TERF rhetoric, so bear with me.

Ditum’s characterization of Cox’s Time cover (Cristian Williams included the excerpt here) exemplifies a recurring problem in trans-exclusionary feminist discourse: the false opposition between trans representation and feminist progress. While ostensibly critiquing media beauty standards, this framing problematically dismisses the revolutionary significance of trans visibility in mainstream spaces. Where Ditum saw a reiterative excess of sexuality, I — along with Williams — saw another unique and necessary thread in the growing matrix of womanhood. Ditum’s dismissive assertion that Cox’s identity ‘changes nothing’ about media representation of women grossly oversimplifies how visibility, presence, and acknowledgment of trans individuals’ existence can be profoundly liberating and politically effective. Cox’s cover reveals how representation undergirds ontological resistance, and to reduce her to the ‘excesses of normative mainstream feminine sexuality’ is disingenuous at best and uncomprehending at worst.

Moreover, Ditum’s argument relies on an essentialist understanding of womanhood that contradicts decades of feminist scholarship challenging biological determinism. It is particularly reductive and insulting that writers like Ditum attempt to speak on behalf of women (including those of us with significant reproductive health challenges) while presuming that other expressions of womanhood cannot be vocal supporters or legitimate speakers on how these issues affect us all. This appropriation of collective identity to exclude reinforces the harmful notion that women must conform to a ‘perfect type’ to earn recognition or compassion — a standard rarely applied to men who are permitted full humanity with all its inconsistencies and contradictions.

Such rhetoric aligns uncomfortably with what Lorde identified as the ‘master’s tools’ — hierarchical thinking that replicates oppressive structures while claiming to dismantle them. By positioning herself as an arbiter of ‘authentic’ feminism, Ditum participates in precisely the gatekeeping mechanisms that have historically marginalized women who did not conform to dominant expectations. As mentioned, these seemingly ‘small’ instances of transphobic language accumulate into larger cultural problems because they reproduce harmful patterns when left unchallenged. Such accumulations gradually sediment into institutional norms that appear neutral but function to exclude.

While issues affecting biological females certainly deserve robust platforms and attention, we can advocate for these concerns without resorting to TERF rhetoric that perpetuates the very power structures that oppress women broadly. This false dichotomy doesn’t simply undermine both causes, it becomes a barrier for coalition building that would produce meaningful social transformation for all. Collective liberation can only happen when we stop imagining that womanhood and women’s experiences are exclusively tied to biological experience; this is only one avenue of subjection — Ditum doesn’t seem to care to see the full picture at the expense of others’ humanity. ↩︎ - There is a dearth of literature on the desexualization or feminization of Asian men.

Specifically on Romeo Must Die & Jet Li, see James Kim, “The Legend of the White-and-Yellow Black Man: Global Containment and Triangulated Racial Desire in Romeo Must Die” (2004).

For more on the desexualization and feminization of Asian men in Hollywood and popular culture: Nguyen, A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation (2014); Eng, Racial Castration: Managing Masculinity in Asian America (2001); Lim, Brown Boys and Rice Queens: Spellbinding Performance in the Asias (2013); Chen & Yorgason, “Redefining Asian Masculinity in the Age of Global Media” (2018); Jung, Korean Masculinities and Transcultural Consumption: Yonsama, Rain, Oldboy, K-Pop Idols. ↩︎ - The rest of the chapters’ lengths are as follows: Lindsay, Amy, Chyna, and Jen’s are 25 pages; and Britney’s opening chapter stands at the shortest with 24 pages. ↩︎

- Image Otherwise, “Imagine Otherwise: Amber Jamilla Musser on Valuing Embodied Knowledge,” 03:38, YouTube, posted on July 17, 2019. ↩︎

- MTV News, “Remembering Aaliyah & What She Hoped Her Legacy Would Be,” YouTube, posted on December 25, 2016. ↩︎

Leave a comment