Every year, I have to assess two things: one, how interesting can I make it for my students when I give them strategies on good argumentative writing tips and two, if I need to revise how relevant it is to combine 90s media pop culture with art-related knowledge. I always say I’m not going to bore my students with anecdotes of things I grew up with (spoiler alert: we do it anyway, typical old people), that I won’t synthesize the same material & tell my students I do so because it’s been successful for nearly four years (hint: it has happened ad nauseam), or that I will find a better way to get students to become better critical thinkers by trying to bridge to the latest social media craze with writing.

I actually never do any of this because I have learned — as a former disenchanted, perpetually online Youth myself ™ — that I am no longer a member of the cultured class. I discovered this rather quickly when I would talk to my younger siblings and asked them to explain post-COVID slang. I taught a writing class on 90s media culture (West vs. East Coast rap, the O.J. Simpson trial, Living Single & the increase of Black-centered network programming, the fear of Y2K, rise of independent films, etc.), and I was trying to convey to my students how language shifts, but meaning is reallocated to those new terms because of sociocultural circumstances that might dictate it — e.g., the rise of TikTok was ‘cooking’ Instagram and Twitter1 but I remember our equivalent being something similar to “roasted.” Gen X seemed quite similar with “toast” if my parents remember correctly.

Anyway, the more I tried to create 1:1 analogy for my students, the more mortifying it was that I was becoming the real-life version of “How do you do fellow kids?” It also felt remarkably similar to Krokus’ comic, “life of a meme,” so I figured out that… there is no good possible recourse to modify my material without having to completely readapt it and risk embarrassing myself with revamping it every single year (since slang, like 21st century popular culture, bear remarkable resemblance to microtrends that quickly fizzle as quickly as they started). And the benefits of seeming ‘relevant’ to my students seems a little less pertinent for my job as an instructor — although I still love last year’s students for giving me a good primer on “it’s giving… depression” and “not me being obsessed.”

I’ve had to teach excerpts from Hall’s “Encoding and Decoding in the television discourse” (1973), and I was trying to explain this connection with melodrama obsession to my husband. We recently taught work by Linda Williams, who has devotedly advanced scholarship on the connection we, as viewers, have with melodrama, film, and race — such as “body genre,” which evokes and produces bodily response in us (the basis of “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess” (1991). She’s written extensively on how the representation of race, gender, and the dialectical signification that emerges through the intersection of such functions in our world — something she’s done in Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson (2001). Either way, he’s not much of a sports person, and neither am I, but I told him how intentional marketing is when they advertise, announce, and/or promote just about anything in and through television. We talk a lot about how NFL teams are identified by a titular individual, the proclaimed “champion” that performs an image for an audience; these chosen individuals become an idealized portrait for what they believe their team and its identity evokes and produces.

You have Patrick Mahomes from the Chiefs, who is the quintessential “Golden Age” Chiefs quarterback — someone who has helped steer the Chiefs into Patriots-esque territory; his buzz on draft day buzz was a murmur, a presumed “high ceiling, low floor prospect” which morphed him from a dark horse into the team’s golden goose. My dad has been a lifelong Bills fan2 (I was born during the Bills ‘back-to-back-to-back-to-back Super Bowl losses’ era), so I am swimming in the Josh Allen mythos that was a part of our household — from rural farm territory California, his humble beginnings have made his spectacular rise as a top NFL quarterback ‘impressive’ to watch. I say this simply because, as someone who studies visual culture, performance studies, and human relationships within these cultural practices… it’s a fascinating example of American exceptionalism wrapped up into the very idea of “spectacle.” We love spectacle. We need melodrama because it produces corporeal response within us that becomes a part of our identity. I won’t go too in-depth to the nature of the rivalry between the two (I’m exhausted, okay? I have heard about rivalries my entire life — USC v. UCLA, USC v. Notre Dame, Ducks v. Kings, USC v. Oregon, Bills v. whoever my father despises, Real Madrid v. Barcelona, etc.), but this was only one example of something that reveals how invested humans are in two things: one, the symbolic construction of a ‘hero’ through a curated narrative and two, that popular culture requires personal, deep investment into helping establish and endorse those kind of symbolic constructions and interventions.

Williams says it quite well in her chapter, “Melodrama Revisited,” where she discusses the role melodrama plays within our society. For example, she states, “As a result, melodrama is structured upon the “dual recognition” of how things are and how they should be. In melodrama there is a moral, wish-fulfilling impulse towards the achievement of justice that gives American popular culture its strength and appeal as the powerless yet virtuous seek to return to the “innocence” of their origins.”3 If we take what Williams says and map it over Mahomes-Allen, we see how American sports culture purposely constructs narratives that are twofold. The ‘how things are’ account puts their records against one another and produces speculative outcomes in terms of their championship possibilities — the likelihood of how these statistical comparisons will convert those win-loss records into tangible trophies as byproducts of those ‘objective’ materialities. However, the idealized ‘how they should be’ perspective is a subtle and painstaking endeavor that undergirds the reality; American viewers perceive small-town farm boy Allen as the inverse of ‘dynasty-heir’ and ‘nepo baby’ Mahomes.

This does not mean I take these things to be entirely true, but media produces these athletes as constructions which put one another under pressure: Allen is an underdog, not simply because he clawed his way into substantiating his competitive nature and athleticism skill, but because his ‘raw talent’ is part of an unsuccessful empire. As the offspring of an unfortunate Bills devotee, I know that between the years of 1994-2019 the Bills’ win-loss record was abysmal; only seven times it seems their seasonal wins were greater than their losses. I know that their brief success in the 90s was with quarterbacks Jim Kelly and Doug Flutie. And I know that the rivalry between Mahomes-Allen/Chiefs-Bills is even more troublesome in our household because my grandfather is a Kansas City-native (born and raised), so it’s depressing when these showdowns occur within our households because the bickering is non-stop.4

Knowing the history of the Buffalo Bills, it converts Allen as the working-class, blue-collar, small-town underdog into a glittering, twenty-first century Alger “rags-to-riches” materialized commodity.

Allen, seeking ‘justice’ for the Bills’ four straight Super Bowl losses — and their own weaknesses to ‘defeat’ the Chiefs in recent years — demonstrates Williams’ “hero-victim” framework. Allen is exceptionally talented and has continued to deliver strong results regarding his physical abilities on the field. He has become the ‘face’ of the Bills franchise and has the humble charisma of a leader who inspires the team — and fans — that he is deserving of success because he is driven to direct the Bills to championships, while carrying the burden of such failures and shortcomings on his shoulders for the teams’ inability to deliver Super Bowl championships. In the United States, where class is an unstable idiosyncrasy but covertly embedded within our culture, Allen’s humble beginnings in rural, central California connect with an American population that perceive him as a world apart from the elitist ‘pay to play’ structure that dominates American sports culture. But also operative in the success of Allen as ‘hero’ is the victimization to which he is subjected to by Mahomes. The Bills are rebuilding, rehabilitating from the perpetual ‘failure’ ethos which has blanked the franchise for three decades; it matters little that the team is a million-dollar and growing franchise when their twinkle is surpassed by the blaze of the reigning Chiefs. Sports media and popular culture are invested in the potentiality of moral value recognition when Allen overcomes the Chiefs dynasty and Mahomes — to not simply prove his talent and abilities, but to redeem the Bills and the wistful fanbase who are invested in their team receiving the spotlight that has so long evaded them.

Anyway — I have these conversations with my husband quite often, and it’s reminiscent of how I engage with my students: you have to establish a framework that not just they understand, but one you are comfortable performing within. The level of comfort, ease, and confidence that I have in teaching and demonstrating examples in this way makes it easier to offer students insight to thinking deeply about their arguments, but also to make them feel moved to push their own imaginative potential. I simply cannot do that if I try to relate to them through their own language and pop culture references. But mostly, I don’t know what’s “in” at the moment. My younger siblings are video game kids, and I know only a handful of students who are invested in that culture (and I’ve learned that some kids are tethered to Fortnite, while others are invested in League of Legends, Call of Duty, Valorant, etc.).

Back to Hall.

I use this example not because it’s interesting; of course, it is interesting — American fanaticism saturates everything, and I think it’s always worthwhile to poke the bear. But because it’s a great example of Hall’s “encoding-decoding” communication model.5 I won’t get into the minutiae of the system through the publication because the purpose here is to help students engage with deeper analysis once they’ve established that there is probably something more going on than what they are simply seeing. The most significant trait about Hall’s encoding-decoding model is that “meaning” and “message” are products (e.g., Allen is an underdog in comparison to Mahomes, therefore he represents a deserved ‘rags-to-riches’ hero story for the American public to look up to/idolize), but we need a framework to ‘get’ them — social practices like where the viewer/recipient grew up, who they engage with/talk to, region/landscapes/environments they’re familiar with, etc.

So, while this example is probably relevant for a select group of students that I teach (i.e., namely students who grew up invested in American football culture and are still moderately in the loop regarding that sports culture), I always follow up that this can get a little mix up and misunderstood for individuals who come from experiences outside of these unique spaces. I.E., we don’t share the same sociocultural, economic, geopolitical ‘experiences’ as one another because United States/American mainstream culture is its own entirety vs. mainstream popular culture that my Canadian, Japanese, Korean, or Indian students experienced. I also appreciate receiving first-hand anecdotes from students when I teach this publication because I don’t just learn about how vastly different East Coast and Midwest experiences are, but how vast Californian culture can be. I loved learning, for example, how common it was for my Midwest student to tell me their Starbucks equivalent was Dunkin Donuts, and that there seems to be a Walgreens on every city block. But it was also fun to hear my Californian-raised students, New York-born, and Australian students argue the following examples:

- “No yeah” = yes (Nah yeah)

- “Yeah no” = No (Yeah nah)

- “Yeah no for sure” = Definitely

As we analyze Hall’s communication model, many are learning phrases like “hegemony,” “hegemonic,” and “ideology” in an official setting for the first time. So, it takes time for them to comb through how these concepts play out, but we always reign it back into the “authority” of the dominant mainstream cultural order — namely, we are operating within the Western/US American ‘dominance’ of that code and the message’s transmission within this circuit.

Spoiler: Not only did I grow up in a sports-centered household, but I grew up with two older brothers who undoubtedly loved comics; naturally, it’s something that I listened to them argue about for hours, back and forth, and scream at one another as they beat each other up in Marvel vs. Capcom. So, I teach my students that these messages are signs, fantastic ‘stand-in’ icons which have numerous meanings. While there can be dominant meanings embedded into these messages, there are always numerous factors at work when it comes to the message’s transmission (like demonstrated with regional slang such as “yeah no, no yeah” or generational slang like “cooked”).

They should be aware that there are two layers when it comes to analyzing “signs” — denotation & connotation. And I always turn to Captain America’s shield for this part.

- Denotation is… quite literally the surface-level meaning of something. It means the literal definition of a thing, a what you see is exactly what it is.

- Connotation is the deeper, more nuanced meaning embedded into that sign. It’s the “secondary meaning” of a thing, its symbolic interpretation.

The denotative meaning of Captain America’s shield is quite literally a shield. In the MCU, it’s a circular shield that is made of vibranium, a fictional metal originating from Wakanda. However, the connotative meaning of the shield can vary, depending on the recipient of the message (image of the shield). The most common meaning for the shield is the defense of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that America is supposed to uphold… [symbolize Cap’s] non-aggression and non-lethality… [Cap] a defender of the innocent, not an aggressor [which given his World War II origins].”6 This isn’t innovative or unusual, given the construction of MCU Steve Rogers who personifies these ideals regularly in film representations. So, for a dedicated MCU fan the shield might represent the resilience and humility of a self-sacrificing patriot whose devotion to and for the good of others parallels a Messiah — a willingness to die for the ideological values of freedom and liberty. Yet, the shield for non-U.S. viewers can indicate American jingoism, masked through the rhetoric of exceptionalism that Captain America embodies. It also illustrates deliberate strategizing by Disney’s MCU-verse to sanitize the West through U.S. American candied military propaganda. Key here is to illustrate to students that a “sign” is rarely only a “sign” for its dictionary-level meaning.

So that my students “get” it, I typically provide many visuals so that information is accessible and straightforward. Given that I teach many students who have not yet learned to annotate and evaluate what information is pertinent and what is supplementary to the ‘meat’ of material I share, I always do my best to do slides that they can follow along and is filled with bulleted “need-to-know” things. I will always elaborate, explain, expand, etc. as I talk to them about these things (I have been doing this long enough that I have about 5-7 different explanations or definitions to reinforce certain topics, and I have about 5+ answers to the many questions I have gotten about Hall, encoding/decoding, semiotics, etc.). I am also an art historian by trade, so incorporating art history is always a bonus for me to take an interdisciplinary teaching approach with my students — a win for us all.

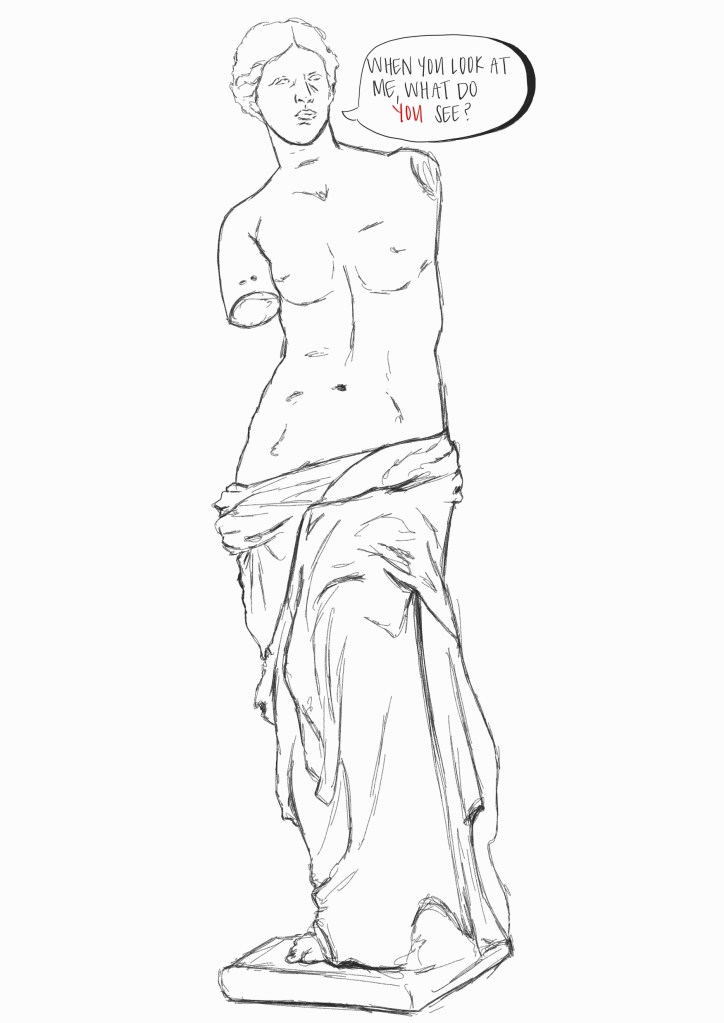

So, another example (with my superb drawing skills on full display, to the left). Here, I just give my students a table with definitions/key points that differentiate one term vs. the other.

| DENOTATION | CONNOTATION |

| “First level of representation” | “Second level” of representation [+ more] |

| It is what you “objectively see” | Idea, embedded intent/perception, and/or feeling which symbolizes that first, introductory/initial level |

| Fundamental, dictionary-level understanding of the thing | Requires a context (which is subjective) that allows for different forms of interpretation |

“Can you give examples of each?” so says a student.

“Why yes,” I say enthusiastically (because I know my students are not thrilled by this lesson at all, but I am!). “Here’s the breakdown –“

A denotation-based understanding of THAT image might be…

- “picture”

- “sketch”

- “drawing of a non-armed figure”

- “drawing of the Venus de Milo statue”

However, a connotation-based reading of THAT image might be…

- “symbol of female beauty/femininity”

- “manifestation of love, sexual desires“

- “ancient Grecian idealization of the ‘perfect’ form (body) in society/culture”

So, when students are committing to close reading and visual analysis, I tell them that they need to have both.

DENOTATION ---> CONNOTATION

How you see/describe ---> How you interpret that thing something what it means

(signifies)

[Objective-based] [Subjective interpretation]Committing to a deeper-level analysis (or what connotation-based analysis is)

Students need a bit of hand holding at times to demonstrate how analysis works, which is fine! I’m good with this, because it means that I get to flex my muscles in translating material into ways that will be accessible and understandable to them. I also think I enjoy this kind of mundane instruction work because I can connect with all students here; some students are nervous, anxious, embarrassed, and/or ashamed that they are not on the same page with their peers. I always dislike when students feel like they are behind or are stupider than their classmates because something isn’t ‘clicking’ for them the way they feel it should be; a big core of my teaching philosophy is that each student has individual needs that should be addressed through my instructional style, and I always re-evaluate what I do or how I say something if I notice or am made aware that something isn’t digestible or clear. I was a first-gen student, the first in my entire family to graduate from university; my classroom is an environment where those experiences shape my teaching approach, and I let my students know that this space is an environment where they are not judged, criticized, or shamed for those experiences coming into that room.

So, we take it to the basics.

If we take that to be a drawing which represents the Venus de Milo statue (where the real-world marble version resides at the Louvre), the next question we discuss is:

“What might the real-world Venus de Milo potentially symbolize (signify)?”

There could be many different ways we could “read” what the statue could ‘mean’ — how we might analyze what its deeper-level interpretation and/or understanding of what it is/does. Students often answer what their own thoughts, impressions, or ideas might be; these range because some have knowledge of Classic Greece, others know it’s a marble statue and that’s all, a few have seen it in person and describe what it’s like to see up close, and a few speculate what it looks/seems like to them. All valuable! I enjoy hearing their answers because it’s a great discussion point for them to see how different perspectives can inform the different disciplinary approaches to a marble statue. I might explain brief differences between semiotics and iconography, but it’s typically only something I would get into with the few visual art/design students that are keen on the more theoretical grounding to ‘reading/seeing’ visual works.

But I give them working examples like:

- An art historian might present an analysis of the statue as representative of aesthetic choices and design trends that convey idealized Grecian beauty, depicted in a three-dimensional (in-the-round) format. It is one example of a style that was dominant/preferred during the statue’s creation.

- A cultural anthropologist might examine the statue as symbolic of Grecian ideals (e.g., a specific society’s notion of beauty, femininity, highest form that Grecian women should seek to emulate/copy, etc.). But is also represents a sociocultural object materializing “work”; the statue illustrates the kind of labor that the ancient Greek community/culture prizes as important or valuable.

- For a Greek citizen, who lived during the Classical period, it might just potentially be an example of the female body. [We don’t exactly know what they thought, but we can work from documents, records, visual works, etc. that survived and present hypothetical circumstances!]

- We could speculate that Greek citizens perceived the statue as an earthly incarnation that inhabited the temple, in place of Aphrodite (Roman’s Venus). The statue becomes an idol, a vessel that is revered in place of the deity/goddess.

- And my favorite: a child (like my younger brother, once upon a time ago when I was taking my first History of Western Art class) might go … it’s a naked lady!

These various interpretations occur through different contexts that allow us to imagine that drawing of the statue to mean different things during different times. These connotations can and do occur through what Hall called “codes.” These codes are important for students to recognize, because much like the analysis of Josh Allen, Captain America’s shield, generational & regional slang, the Venus de Milo, and subsequent visual analysis that follows here, they help us interpret and make sense of our environment. This communication model that Hall proposed — transmission, interpretation, and understanding — relies on encoding and decoding. These processes depend upon those codes — signs which contain pre-existing and embedded meanings. I even make it meta for them by illustrating that Hall’s communications model was already at work throughout the activity: the drawings, the explanations, the definitions, even just using English as our de facto language… they’re all codes!

Here, I can see the looks on their faces — some flabbergasted, some intrigued, most are counting down the minutes until they can leave because it’s 8:30am and they didn’t sign up for this. But I like to tell them that another important characteristic about this communications model is that the ‘dominant’ code stays dominant not determined!

Much like the analysis of Josh Allen — the California farm boy wonder — and the dialectical nature of Captain America’s shield, we need to recognize that mainstream codes are not fixed; interpretations of events are certainly not static because we revisit them constantly and they can change and fluctuate (a lot of this relates to Williams’ concept of “structures of feeling,” which I might quickly cover). But what students should take away from Hall’s model is that meanings are preferred because they have become engrained, embedded, and imprinted onto our idea of that’s just the way it is; the struggle is overcoming the power and authority that is injected to that code. But there are three hypothetical positions that a receiver can do with that sign/message (and that applies here!):

- Operate within the dominant code — U.S. citizens perception of 9/11 as an act of terrorism; U.S. propagating military interventionism in Latin America as combating communism; Captain America’s shield is representative of democratic values, like life, liberty, justice, fighting fascism; Josh Allen is the determined underdog.

- Negotiate with the code — a U.S. born-Latine/x/a/o child observing U.S. military intervention as a ‘necessary evil’ to put communist-backed regimes under pressure, while acknowledging the consequences of U.S.-funded paramilitary death squads (like El Salvador); acknowledging the underdog narrative that propels Allen vs. Mahomes, but recognizing the privileges that both quarterbacks have within their respective sports establishments

- Decode the message in a contrary position — Rejecting the rivalry between Mahomes and Allen as a manufactured spectacle for increased viewership during playoffs; Captain America’s shield is American corporatized propaganda that valorizes the military industrial complex. My other favorite: Black Panther is not a cinematic masterpiece celebrating Black radicalism, despite featuring an all-Black cast (behind & off-screen); it is a visualized bait-and-switch with pro-CIA propaganda and Killmonger is a misrepresentation of Black Marxism.

The use of codes is far-reaching, and students should ideally be able to identify a few on their own (I give them a few minutes to come up with examples of their own, and I always ask for volunteers to hear how culturally diverse many of them are!). But codes can and do change; however, they should recognize that codes can only be ‘successful’ if that code is shared between the creator/producer to receiver/interpreter. I break it down as many times as possible for students to see how detailed and minuscule they could imagine our “shared code” to be — understanding English (like knowing The Rules of sentence structure, grammar, common terminology in writing), working knowledge of Hall & cultural studies, experience and know sociocultural attitudes of the 21st century, etc. This is where I get to have fun with them.

The

How might this be used for close reading and analysis?

Okay, I’m a 90’s kid. My students learn very quickly that I am on the old(er) end of the spectrum; at first, I thought this was a terrible thing to share with my students because I wasn’t ready to be “the old” one. However, I have quickly learned that being in my thirties is fantastic (being financial stable does wonders for your health); I also quite like that my students are aware that I am not their friend — the further away in age I am from them, the better it is for me. I have yet to have a student challenge or question me the way they have some of my younger colleagues (which is an unfortunate eventuality in academia), so I believe establishing this gap early on in my classes… the better it is for the both of us. I also quite like setting firm boundaries at first because it’s much easier to ease them as the weeks pass, rather than attempt to develop constraints later on once they have taken advantage of those limits. Anyway, I grew up with The Simpsons and every Halloween we looked forward to their “Treehouse of Horror” episodes. In particular, one that remains my favorite to this day is their version of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” (1845) The specificity to stylistic choices that blend The Simpsons style with the tone of Poe’s writing is my favorite way to teach visual analysis — especially exploring this with my students and how these aesthetic choices create a “tone” (an attitude) that produces a mood to convince viewers how to receive/see the short.

I give them the basics of the interpretation. So, I explain that while James Earls Jones narrates the poem as a voice over, Homer is the unnamed narrator for who he is speaking; Bart is our beloved raven. Quite a few of my students have never watched The Simpsons, so I take the time to discuss the central theme of grief through the loss of the narrator’s love, Lenore. As the unnamed narrator dwells on his loss, the raven which taunts him is the materialization of feelings — the inability to move on from this painful loss, the realization that the unnamed narrator will never see the beloved Lenore again. The Raven evokes a sense of disquiet, what it means to be “haunted” by feelings of grief, suffering, torment, the overwhelming melancholy that can cause one to lose sense of their sanity and grasp of reality.

I make a general claim here of something I think I’d like to explore; it might happen, it might need to adapt. However, I tell them that there has to be something that I will keep as the “focus” of my analysis, of what I am engaging with, how I am seeing something.

Hypothetical claim: “The Simpsons’ adaptation of The Raven uses comedic exaggeration to explore how paranoia manifests in the grief process.

“How do we start this?” Students may ask. Well, let’s take it back to how this all started — what is the thing?

STEP 1. What visually shows the mood of disquiet and paranoia?

Ask any of the following questions when ‘reading’ a visual object:

- What do I see?

- What looks interesting to me?

- What details seem important to me?

- What is happening?

- What catches my attention? What am I focusing on?

- How am I looking/seeing this? What am I looking at?

The purpose of the first step is to see — what’s there, what’s happening. Students need to get familiar first with what they think is “stating the obvious.” I call these ‘you-know-what-I-mean’ -isms because students fail to grasp the dangers of asking readers to make an intuitive leap within their analysis/evidence to the conclusion they come to. They think, “I’ve included this quote — a reader should get it.” And feel that the job is done because how could a reader misinterpret what they find to be completely obvious? These become great teaching moments because I was raised as an overthinker; I will overthink and overanalyze any piece of evidence until someone tells me they’ve had enough of me writing about the distinctions between crystallize and materialize. But the point I make here with students is that everyone sees differently, therefore readers will think differently than themselves. It’s always a good idea to clarify and clear up any ambiguities that will weaken the strength of their observations and their argument.

Rather than nudge to a reader and go, “Hey — you get it, right? … Right?” They should always assume that the reader needs to be guided along, given explicit directions on how to get from the start of their argument until the concluding remarks. And this starts with them learning how to be specific about what they are seeing and getting comfortable with straightforward description. Even as someone who has spent the last ~8+ years describing popular visual works, performances, music videos, films, sequences, short films, etc. it feels silly to have to explain Manet’s Olympia (1863) or the organizational structure of the Mixtec codices, particularly when my intended audience is familiar enough with these objects. However, I have also learned through these years that we all notice various details, and some seem infinitely more exciting and interesting than others. I want my readers to know why I find the genealogical documentation interesting in these pictorial works, so I tell my students that their readers should be aware of why they should be interested in what they are arguing or examining. And besides… nothing is more interesting or exciting to me than reading a piece of writing written by someone who is captivated and enthralled in what they’re arguing/examining. It makes me want to be interested!

STEP 2. What details are assisting in illustrating that feeling of paranoia?

Here, they might start to really notice how these visual elements become deliberate choices — they’re cues for an audience to be convinced, without overtly trying to do the convincing. Perhaps it is obvious, and that’s worth exploring here, too. But much like a puzzle, students get to pick which pieces matter the most to them to support those observations (claim). Is it…

- The colors?

- The set design?

- Costumes?

- How character(s) move/interact with one another? With an object? With their environment?

- Facial expressions?

- The framing/chosen style(s) of shots?

- The music? Sound?

- What viewers don’t see?

- An animation style?

- A recurring symbol/motif?

- The tone?

- A hyper stylized aesthetic choice?

- The editing?

- Diegetic vs. non-diegetic sound?

AH! So many choices… HELP!

When doing close visual analysis, students realize a lot is going on — it’s almost like there is too much information and not enough time (or writing space) to get to it all. When students get to this part, I always tell them: scale down and prioritize. Really ask yourself: which features are the most interesting and/or significant to you? And how do these interesting bits support or help with that claim that is being put forward? I give students some general numbers that they might keep in mind, depending on the length/organization of whatever piece of writing they’re committing to. For example, 2-3 features/details tend to be a good starting point for shorter analysis response(s)/essay(s). However, I might suggest that they try to group them into categories — like costume & set design would be elements that support the design’s direction, and camera angles/editing would contribute to the technical elements that reinforce the visual work’s objective.

STEP 3. Determine the direction the analysis takes.

Here, students have the opportunity to be creative and control how their analysis and argument will unfold. But they need to be aware that visual analysis requires these details from above (color palette, editing, music, editing, perspective, medium, etc.) are what is going to prove that claim/purpose. Ultimately, analysis should be structured to focus on a specific theme, concern, issue, observation, consequence, insight, etc.

Lately I have been teaching film analysis rather than traditional art analysis, and both require different needs. I’m trained as an art historian, so ‘traditional’ art analysis (like paintings, photographs, sculptures, mosaics, illuminated manuscripts, scrolls, etc.) is a pre-existing basis that I build from when I do film & performance analysis. In traditional art analysis, the focus is on establishing a relationship between technical visual elements — like line, shape, form, value/tone, texture/surface, positive/negative space, medium, etc. — and principles of design, like emphasis, dominance, movement, contrast, proportion, balance, and so on. This relationship creates meaning, and it’s through those values that this meaning is communicated.

Film analysis can include these static elements but isn’t necessarily dependent upon them in the same way that an oil painting or marble sculpture is. This is not an evaluative position on my behalf! I work across multiple mediums and visual objects, and I am grateful for the skills that this background has afforded me in teaching moving pictures/film & performance analysis. Another aspect that’s provided me a different approach is that I worked several years as an assistant costume designer in theatre productions, so I worked closely with the set & light design crew, the director, the sound operators, the stage manager, and so on… I see things much differently knowing that each wardrobe piece is carefully selected, and I have had to make those choices between symbolic intent & practical functionality onstage. I actually miss it terribly, but that’s a story for another day.

Regardless, my background as an art historian has trained me to be critical and incredibly detailed to notice the smallest things. Knowing how color theory and space balance are used helps me determine the significance for interspersing a full body shot with establishing shots. Having working knowledge of shadow & light makes it easier for me to teach students the techniques & intent of the film noir style. Art history’s formal analysis — like line, form, tone — is adaptable to film analysis, particularly determining how these elements can construct meaning, mood, experience, and/or tone in a film sequence.

But most importantly, art history is not just examining, analyzing, critiquing, or evaluating visual works; it asks us to think about the connection these visual objects have with their respective creation periods. The immediate example I think about is the rise of Impressionism in 19th-century France and how this stylistic change reflected the sociocultural and economic circumstances of the late 1800s; it isn’t just what happened during the art movement’s period, but historical events that preceded it. Haussmannization fundamentally changed Paris in the mid to late 1800s, which widened boulevards, standardized building sizes, rearticulated infrastructure to the city. These new boulevards created new spaces of modern urban life, but they also created a new economic class (petit bourgeoisie) and subsequently, the rise of leisure culture in spaces like café-concerts, country getaways, department stores.

Similarly, the advent of photography influenced how artists saw the world and responded to new, developing technologies to produce visual works. For example, premixed oil paints not only made outdoor painting (plein-air) accessible, but also created vivid, bright palettes possible that reflected the birth of industrialized modernity. Railways and trains made leisure culture possible by connecting Paris to suburban environments, like Argenteuil. Gas and electric lighting produced artificial radiance, lining the Parisian arcades that remained.7 What I am trying to convey is that the artistic traditions — ‘movements’ — draw from, respond, and/or are reflective of their respective cultural moments. Historicizing is fundamental in art analysis, and performance & film analysis is no different.

Where film analysis does differ is that there is just more to look at — more details, more moving parts, more relationships and layers, more things to look at and ‘see.’ As I mentioned before, students should develop observations into “categories” that will help for two reasons. One, they streamline their path to connect these details (observations) around a theme, issue, concern, consequence, problem, insight, etc. Two, maintaining that focus is much easier to do from start to finish when they have an organizational blueprint!

I will include my examples in part two, as I didn’t realize how overwhelming this had already become! And it will include more images, which can slow down the process and make it difficult to follow along. I’m quite excited about the next part, because that is where I combined my love of The Simpsons’ “The Raven” with German Expressionism.

I am going to try something new here since I think it’s valuable to summarize & clarify what the objectives are in my writings.

Important takeaways:

- Effective analysis requires both surface-level observation (denotation) and deeper, interpretive meaning (connotation); college-level analysis asks students to move beyond describing what they see.

- Hall’s encoding-decoding model (communications model) should reflect that meaning embedded in ideas, beliefs, imagery, etc. aren’t fixed; rather, they are influenced by social, cultural, and personal contexts. However, these messages can be accepted, negotiated, or rejected based on the receiver’s position.

- Teaching analysis should guide students to:

- Start with basic observations (“what do I see?”).

- Identify specific supporting details — learn to just see and look at something as it is.

- Group observations into categories that are meaningful or useful to the writer.

- Consider historical and cultural context.

- Be specific and clear about connections rather than assume readers will make those same connections (“you know what I mean”).

- Prioritize observations to what they find significant or meaningful rather than try to analyze everything at once (students assume more is better, when more can be detrimental to their writing’s focus & purpose).

- Teaching with examples that are relevant to oneself makes it easier to teach the material (it’s okay to not be hip and cool — embrace the stability & authority that age affords us!).

But, until then — happy holidays!

Notes

- I have never referred to it by its post-Musk name and never intend to. I’m a creature of habit — oh well. ↩︎

- Author’s note: I have never discovered a definitive reason as to how my Latino father — from Central America, who grew up in Southern California in the late 70s/early 80s — became a Buffalo Bills aficionado. We were never a Dodgers, Lakers, Clippers, Kings, UCLA, or Rams household. Nary the Raiders or Chargers, either. But I did grow up rooting for USC as a kid, so there’s that for hometown pride? ↩︎

- Linda Williams, “Melodrama Revisited,” in Refiguring American Film Genres, ed. Nick Browne (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 48. ↩︎

- Also, fun side note: my grandfather has been a fan of the Dodgers pre-Los Angeles, and my dad is a die-hard Yankees fan. The World Series this year was… something. And no, I also do not understand this turnout either. ↩︎

- I briefly add how the emergence of Hall & cultural studies during the 1980s wasn’t a coincidence! They ought to know that Hall wrote from a very particular set of circumstances and experiences in post-war UK/British society, where cultural theorists were examining concerns that paralleled the Frankfurt School. How do we (societally, culturally) investigate the effects of culture as a mass industry itself on the working class? Hall is so fundamental to this discipline, and my own research, because he — along with other early cultural theorists — were exploring the dynamic of emerging subcultures whose attitudes, ideals, values, and traditions were breaking away from established class consciousness and culture. Popular/mainstream culture becomes tooled and interwoven with power and social issues, particularly identity; our dilemma lies in our inability to ‘capture’ true and real representations of these events, values, places, etc. because they can shift and adapt, depending on who or what is transmitting or relaying that message. ↩︎

- Johnny Brayson, “The Untold Truth Of Captain America’s Shield,” Looper, September 24, 2019. ↩︎

- For further interest in modernity, I highly recommend Benjamin’s The Arcades Project. It’s an unfinished publication filled with different quotations and excerpts, categorically grouped, that tries to capture the ‘feeling’ of late nineteenth-century Parisian society and culture. ↩︎

Leave a comment