“This example [Twitter user @LewieGroh and others expressing disapproval of then eleven-year-old Sebastien De La Cruz singing the National Anthem at the NBA Finals between the Miami Heat and the San Antonio Spurs] illustrates the relationship between race, geography, national culture, and aesthetics within the context of Texas. And certainly Texas is an ideal site on which to transpose the nationalist scriptings of the United States, for Anglo Texas, in particular, “has always been given to a sharp and mythological exceptionalism” rooted in notions of freedom, an independent spirit, bravery, and greatness (Limón 2011: 112) — everything is bigger in Texas. This distinctly ethnoregionalist nationalism impels Texas to imagine itself not as constituting part of an imperial project but rather as having freed itself from a foreign empire, Mexico. In this way, Texan exceptionalism operates as a microcosm of American exceptionalism; however, its uniqueness is also contingent on the perceived “difference from the racialized and stigmatized presence of people of Mexican origin in the state” (112).” – Alex E. Chávez, Sounds of Crossing: Music, Migration, and the Aural Poetics of Huapango Arribeño, p. 199-200.

“Tell me, can you hear me now?”

– Beyoncé, “AMEN”

Beyoncé has always repped Texas – Houston outlines her work, its presence a haunting specter that provides comfort for those who recognize the body of the Southwest through her artistry. (I’m always very surprised1 when people disregard Bey as a product of ‘country,’ simply because she doesn’t obey their criterion.)

However, much of that imagery which she claims – the Southwestern landscape that she evokes, both overtly and deftly – becomes trivialized. This image becomes a facade, purchased when confronted by the ephemera of the contentious, and quite contradictory, introduction of the glittering, illuminated presence of Beyoncé the Mega Superstar. Despite having “roots” within the space of the South, from Texas, her iconic status and celebrity aura have overpowered the connection that Beyoncé has with the territory of Texas and to Houston. Over the last year, it’s impossible to refute these allegations with the birth of Part II: COWBOY CARTER. There has been a deliberate erasure and subsequent denial to that relationality, a kind of denial where regional and spatial colloquialisms tethered to a Southern identity are disconnected and denied to Beyoncé, simply because her presence is antithetical to what “the South” is about.

The last nine months have been revealing of something which many (including myself) have felt growing up as someone whose identity was, and at times still is, incompatible with the jingoistic culture that permeates the United States. But this isn’t a story about me. This is about sinking into the archive of discomfort which I believe the artist is tapping into very well — and the unavoidability and the pain which trudges behind it.

beencountry.com is symptomatic of the denial that impacts specific individuals. And I believe that Beyoncé is forcing us to reconcile that the consequences of such acts are permanent and inescapable. Whether anyone else is paying attention — I was. And I still am.

It is a confrontation of how and at what moment is ‘origins’ denied? And importantly, who is the arbiter of displacing individuals from these sentiments? I ask, too: what does it mean to “be” country, what happens when we ask about who continues to be impacted by this rejection, and for what (or namely, whose) purpose does this benefit?

I open these questions to turn to Chávez’s writing2 around huapango arribeño and how the musical genre itself functions as a border crosser. It’s a fantastic book for numerous reasons, specifically one is selfish, as someone who grew up in this forever-in-between world as a U.S. citizen and the child of Latin American immigrants. However, the fundamental reason why it is such an excellent read is that the book explores how the sounds of a Mexican regional music style can cross borders, boundaries between different nation states, and inscribe places, environments, landscapes, and attached vulnerabilities and anxieties from one place to another. Chávez describes it as “people carry locations with them, here and there,” and I believe that’s what’s significant about music. It is the ability to carry these environments within itself, collecting people and experiences from one space to the next. It’s the creation of a “language” that conveys a way for others to recognize and feel that resonance – a system that does not simply sustain the prioritization of division, but the real ways in which landscapes are inscribed in and through sounds. What Chávez also identifies is how individuals can be categorized as “un-belonging” when there is the slightest prospect that it might challenge or threaten the mythos of a nation-state. Border-crossing is not about the peril that occurs with perceived vulnerabilities of a specific state (here, I am thinking deliberately of the United States and Mexico), but about the disruptive potential of “in-betweenness” that becomes a problem of the individual – to be displaced.

In particular, beencountry.com’s May 1st update is a sharp reminder of the losses which afflict individuals that only matter through their accumulation.

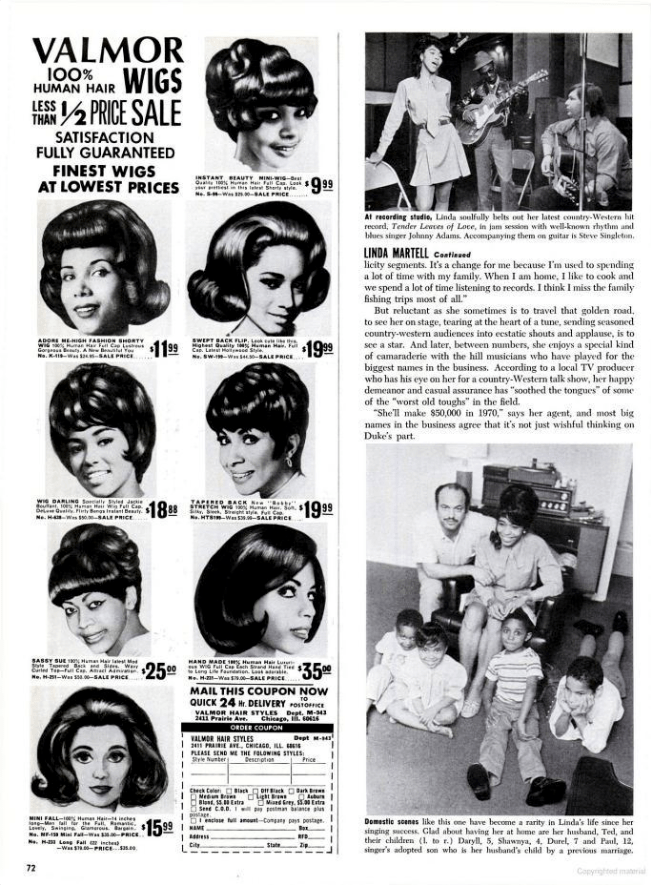

For those steeped in the history and lore of Beyoncé, there is the photographic aftermath of the event that led to the development of Cowboy Carter (the photograph with The Chicks). However, moving clockwise, starting on the bottom left, the beencountry.com update is as pictured: a red and white embroidered patch that says “★RODEO CHITLIN’ CIRCUIT★;” a close-up image of Beyoncé wearing a Linda Martell shirt during the signing of Cowboy Carter albums at the Supervinyl store in LA on April 12, 2024; a modified promotional image of Linda Martell in 1970, the original photograph by Isaac Sutton; 1968 photograph of the Gadsden High School basketball team, highlighting Mathew Knowles; a photograph of Beyoncé and The Chicks from the 2016 CMA Awards; and a gif from the promotional video “BTS: The Formation World Tour (Houston),” posted on September 22, 2016. The six images reflect upon the creation of self, subjectivity vs. objecthood, and the relationship that the constructed self has with nationalist sentiments. In particular, they speak to the realities of bodies placed under violence and trauma, and the experiences of Black womanhood through the legacy of an American ethos that posits Black subjectivity, a sense of being, as tied to its fungibility, its value, to continue the pursuit of nation-building.

beencountry.com is supplemental to Cowboy Carter, but it also is informative to how we might read and anticipate the three-act journey by Beyoncé. At first glance, the photos are an assemblage of historical and personalized snippets, curated to give what we might see as brief, autobiographical insight. The initial function of the website is a pastiche, a collage of imagery that guides viewers to thinking about how Beyoncé is claiming specific “spaces” and accounts as integral to the process of identity-making. However, it’s rather disingenuous to assume that the website only exists as a “scrapbooking” effort by the artist, where Beyoncé deposits visual works to preserve, present, and arrange these snippets as part of her identity — a journal of memories that cultivate and birthed Cowboy Carter and the present visual rhetoric of Act II: Beyoncé. Recognizing that the final update came on Juneteenth 2024, we can infer that the assemblage functions for a very particular reason. And its publicization is not just a ‘spectacle’ that we are passive viewers, enthralled by the juxtaposed assemblage of indiscriminate visual works; Beyoncé uses each update to present what I call ‘inescapable consequences of denial.’

Yes, it isn’t hard to imagine that beencountry.com is indeed an album of artifacts that Beyoncé wants to display, to reveal the legacy of Black people and their contributions within the framework of the U.S. empire3. But Beyoncé has multitudinous expressions of self, and beencountry.com is demonstrative of how Beyoncé as Artist and the Businesswoman coincide. To read beencountry.com as a trivial vessel through which she documents photographic and visual works synonymous to aesthetic objects is a disservice to the kind of artistry and branding which she commands. Entrenched in Beyoncé’s work enables me to highlight that her decisions are not without requiring us to suspend our disbelief of celebrity culture, that her presumed ‘creative kitsch’ is only capital to continue to elevate her brand. Whatever society might assume about Beyoncé the Businesswoman often does not cooperate with Beyoncé as Artist; she pokes at a global audience — one invested in, apathetic to, and resentful of her presence that lingers.

Announcing Cowboy Carter during the 2024 Super Bowl was a choice — calculated and crucial. It’s a maneuver that is affiliated with the Beyoncé brand — those in the trenches of popular culture recognize that Bey has a pattern which has been converted into a trope of “stunt mode.”4 For example, there was the frenzy following the surprise drop of Beyoncé (2013), accompanied by an entire accompanying visual album, released without warning or press that produced a signature of “surprise ‘drops’” for future musical releases. Let us not forget that Beyoncé’s impact is transnational. Beyoncé‘s unannounced drop became a catalyst for shifting musical releases from Tuesday in the United States, Mondays in the UK and France, and Fridays in Germany to a worldwide standard of Friday in 2015.5

The public received libidinous, vulnerable, Yoncé in 2013 once the global audience was introduced to her alter ego, Sasha Fierce. There is disagreement as to the genesis of Beyoncé’s visual albums; some argue that the creation of accompanying audiovisual albums began with B’Day Anthology Video Album but became a cohesive vision with the eponymous album. Others maintain that the birth of the audiovisual album only emerged when they recognized Bey’s intentionality guiding its construction.

As Sasha Fierce, Beyoncé produces and transforms into an avatar that performs an exploration of a self for an audience.6 Future multimedia audiovisual companions are the imprint of her artistry and artistic legacy — Lemonade in 2016, Homecoming: A Film by Beyoncé in 2019 documenting her headlining the 2018 Coachella Festival, Black is King in 2020 as visual companion to Disney’s The Lion King: The Gift in 2019, and last year’s documentary Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé that followed the 2023 Renaissance World Tour. These are signature moves which mark the artistry of Beyoncé between multiple sensations. Her identity is bounded, as a musical artist who is at the same time an enactment of spectacle and elusiveness but also a figure of anticipation that fulfills some kind of phenomenon of shock. Beyoncé commits to these acts to impact an audience, but to also redraw the frameworks that have become utilized to understand her “brand.”

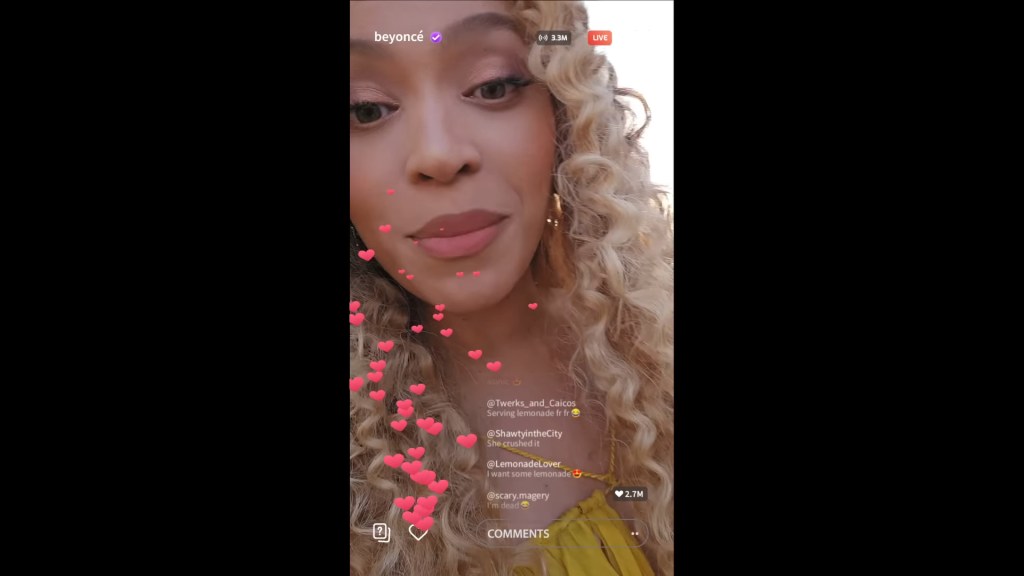

In order to ‘understand’ beencountry.com, viewers must acknowledge the “inconsistencies” that are part of her artistry. Converting the work of Beyoncé into ‘tropes’ does not minimize the impact of how she uses popular culture to linger in between the roles that she enacts — as artist, subject, participant, Black woman, businesswoman, American, as creator, as performer, as spectacle, as strategy. What is interesting about the formation of beencountry.com is that it hinges upon the commercial “Can’t B Broken.” It pokes fun at how Beyoncé markets her techniques to innovation and creativity, challenging the experiences of virality; we see her move from an innocuous gesture of a lemonade stand to developing a video game streamer account, even attaching herself to the Barbie zeitgeist of Summer 2023, and proclaiming a nomination of “Beyoncé of the United States.” Perhaps these activities are not clever, they are gestures that sensationalize a persona that must continually seek reinvention in order to be relevant and interesting. Yet, the awareness which undergirds her performative acts inform us that she is both novel and overdone, ostentatious yet discerning that her shortcomings are a direct result of her own doing. Beyoncé eclipses Beyoncé, and it becomes a never-ending oscillation between who Beyoncé is, what Beyoncé seeks to be, and how Beyoncé elects to be perceived — and consequently, how Beyoncé thrills beyond pseudo-predetermined expectations.

Let’s start with the overt: the GIF from the promotional video, “BTS: The Formation World Tour (Houston)” on September 22, 2016.

Three GIFs have preceded this variant on beencountry.com, but this one operates differently. Eppink suggests that GIFs in internet culture are used in service of the needs of individuals who are immersed in the ‘online world.’ In particular, GIF usage addresses an identity-making process, a ‘cinema of affiliation.’ Eppink states, “The result is a digital slang, a visual vocabulary unencumbered by authorship, where countless media artifacts are viewed, deployed, and elaborated upon as language more than as art product.”7 Beyoncé maneuvers this language as part of lexicon which she exploits, actively using the GIF as an artifact which recontextualizes what this ‘moment’ represents.

The GIF is a method of expression, transforming this moment from Houston’s The Formation World Tour date — as viewers, we see what appears to be a grand entrance. Shadowy background dancers parade in a successive row behind Beyoncé, hints of their bedazzled leotards peeking out with the lighting. Beyoncé drags the white fur coat behind her, like a cape it flows behind her as she saunters down the stage’s steps, the golden microphone reminiscent of a drum major’s mace. As she looks to her right, she conducts the dancers to fall in behind her with a smile on her face — not simply a smile of happiness, but of pleasure and jubilation. You can almost hear the laugh as she saunters from the upper level of the stage. In this moment, the GIF reveals a moment of elation in her body movements; we don’t know exactly what she’s smiling toward, or even why she is so pleased in this exact moment. But we can feel this moment, producing a collective experience through Beyoncé’s delighted expression as she moves closer to the fans who crowd NRG Stadium.

Yet, why place this pleasant moment with Martell’s altered photograph and her father’s high school photograph? For whom does this moment inspire pleasure? As online spectators, we watch its repetitive looping — a never-ending circuit that returns us back to her first step on to the lower stage, ending with her elated expression before it begins again. The base function of the GIF is reiterating the same moment, over and over, endearing us to continuously seeing the smiling Beyoncé. The animation itself is a successful product of its limitations, perpetually stuck in playing the same moment over and over again — the GIF operates as a “performed reaction that are not fully realized until they meet their catalyst.”8 As innocuous as the moving image seems, Beyoncé employs the GIF as a confrontation between an online audience and her image; the encounter reveals the intentionality of its placement amongst the other assembled images. The GIF aestheticizes a gesture that inherently marks a somber moment for Beyoncé — what I’d call the ‘provenance of melancholic denial.’ Its emergence occurs through the assembled nexus of visuals, but its burden concentrates in the endless cycle of the GIF, its undeniability staring right back at us.

What I consider the ‘provenance of melancholic denial’ relies upon the scholarship of Diana Taylor and Karen Roybal9. Taylor describes the “the repertoire” as a strategic process that carries cultural memory and knowledge that goes beyond the constraints of written recordings (‘the archive’). Royal fleshes out Taylor’s concept in “the repository of recuerdos” which are preserved knowledge in the forms of oral traditions, personal objects, and cultural practices. Their challenge is confronting the o the ubiquitous “Archive,” a disembodied framework that prioritizes ‘written’ forms which often are controlled through institutional processes; history becomes a static commodity, hammered into a form that erases the dynamic presence of ‘alternative10 forms of history.’ It isn’t an innovative approach in academic studies now, but it’s something which we ought to continue to chisel at in search of notions that will decenter hierarchic historiographic processes — in particular, our framing of what is or is not legitimate ‘historical documentation.’ However, their approach asks us to deprive the historical record of its privilege and supremacy that meets some arbitrary criteria of ‘valid’ documentation. The creation of The Archive presupposes that the West, the Global North, is the standard to which all other regions fall short of expectations and anything which disrupts hegemonic globalization — or that which jeopardizes the continuous authority of interventionism.

I would like to make it clear that this concept of ‘the provenance of melancholic denial’ is underdeveloped and requires further fine-tuning on my part. However, I argue that Beyoncé uses beencountry.com as a dialogic strategy that reveals and disavows identity-making as an oscillation through excess of a ‘something else’ and the legacies of what has been. There is a profound sadness to a self-aware identity process that is bounded to histories which are not of one’s own making, the subliminal remembrance of difference and attempting to think beyond these deterrents that mark specific human identities. Provenance suggests that there is a beginning point, an exact moment and space that registers this divergence of affective experiences that are in response to intersecting network of power; I do not believe we can suggest there is an origination for how these abstract experiences shape and form the human identity because there is no universal standard to how power maps and spreads itself across humans and bodies. Rather, I believe that the provenance of melancholic denial is generative strategy that minoritarian subjects develop through legacies which are woven into their bodies, their experiences, their politicization and racialization before they can naturally encounter them. But it’s also about recognizing the material effects of trauma through wielding power, and it’s also about confronting other bodies who cannot deceive themselves from what the product of such a linkage does and continues to do. For minoritarian subjects, it’s not simply a continual presence of in-betweenness, tethered to hegemonic ideals, but rather about the inescapability of the reality that this lingering burdens up to continue to seek a kind of something else which absent. We live in the deep sadness, of malaise, of identities which we must protect and safeguard, but one which causes us great pain — to see Beyoncé navigating, resisting, reimagining her identity through a complex network of processes and ideas which occur through pain, resistance, and generative survival. It is to be dis-possessed of one’s own self beyond recognition, but to endeavor to rearticulate oneself through that deprivation.

This emerges in recognition of its presence in the looping image, from a promotional video on YouTube from Beyoncé’s Houston “The Formation World Tour”11 date. It’s quite short, only slightly longer than one minute and is a cursory rundown of Formation’s ‘first leg’s stop in the city.’12 The montage starts with a voice-over and interspersed shots of the stadium’s landscape. A woman’s voice is heard saying, “Houston, Texas, baby,” joined by others. The woman’s chant is laid over a long shot of NRG Park, where we see three mounted flag poles, blowing in the wind — from left to right, NRG Park, Texas, and the United States flag. As individuals cross the sidewalk below the flag poles, we cut to an establishing shot of the front of the arena — NRG Stadium. The shot doesn’t linger on the arena, instead cutting to a panning shot of the crowd outside of the stadium; among the wandering crowds is Matias’ Spirit of the Bull, six Spanish fighting bulls commissioned by the Houston Texans, dedicated in 2003. The shot offers us insight to the location, the landscape of Houston through the stadium’s environment; this is but one zone of Beyoncé’s language to her beloved Texas. This territory is where we see those fusions of Beyoncé — the Performer, the Texas Girl, a Black woman linked to various expressions that mark her identity. It’s in the woman’s voice, her utterance of Houston and baby which becomes a hymn, a crescendo that prepares us for the appearance of Beyoncé the Superstar, but it also declares an example of Crawley’s reimagining of ‘Black culture hermeneutics.’

Black culture hermeneutics are practices which produce tension on the repressive constraints that have defined Black ‘flesh.’ For example, Crawley complicates how the premise of violence is inherently structured into the rhetoric of whiteness and its epistemological delineation over ‘everyday life.’ Our dilemma is not simply combatting the passivity of logics which reiteratively produce Blackness as flesh — rather than the affordances granted to the ‘body’ of whiteness’ — that is synonymous with property, a commodity and tool that advances the enterprise of nationalist sentiments. Rather, Black culture hermeneutics is based on the “ongoing “no,” a black disbelief in the conditions under which we are told we must endure… [Blackpentecostalism is] the performance of otherwise possibilities in the service of enfleshing an abolitionist politic.”13 Similar to the concept of the repertoire, the practice of repository of recuerdos, Blackpentecostalism is a strategic deployment of Black culture hermeneutics that forces a confrontation with ‘flesh’ as a transformative political position, an identity which is enveloped in collective liberation and committed through bodily actions, choices, and decisions. The opening of the promotional video unveils to us one of many sites to how Blackness operates within the framework of the United States, in conjunction with but at odds with its desires of subjugation to anything which does not advance its immaterial needs. We could simply see and hear the chanting as only a chant, a song commemorating Beyoncé’s homecoming; but I propose to see it differently, that it is a site of collective potential and dispossession, to be defiantly Black but still feel displaced from an environment that is intrinsically a part of one’s sense of self.

Formation begins playing approximately fifteen seconds in, but only after we catch two important moments: one, a glimpse of the stadium audience, who wait anxiously for the opening of the main act; and two, Beyoncé holding the stair railings, her head bobbing as one dancer whips her arm up and around in excitement. The moment from the GIF, however, is approximately thirty-four seconds in. The timing of the track is shrewd; near the completion of the first refrain, the line ‘never take the country out me‘ carries Beyoncé down the stairs. This is the initial layer of Beyoncé the Performer, for she extends herself as a spectacle in this moment — what we see as her grand entrance, her saunter toward the audience, is what she wants to be seen. It is cleverly constructed, and she is aware that we are her audience; Beyoncé takes this challenge as a moment of confrontation, and she does it quite flamboyantly — an in-your-face assertion that her possession of ‘country’ is that which cannot be extracted from who she is. She is country, how could this be denied to her? The second level, I believe, is even more impressive and shifts the stakes from performance to the arena of Beyoncé the Artist.

It seems self-evident to start The Formation World Tour with Formation; a politically charged anthem, the song is one example of what we could call the ‘dialect’ that Beyoncé uses to provisionally communicate. The opening of the act itself is polemic. On one hand, the song’s debut marked two crucial, painful moments that catalyzed the Black Lives Matter Movement; rather than focus on the trauma and loss that continuously reverberates within the Black community, the song became an anthem that was unapologetic in its praise for Blackness — and Beyoncé’s command of it to a global market that sought to convert her into whitewashed capital. Conversely, Beyoncé stepped out on stage in a custom Gucci bodysuit, made specifically for her debut in Houston; in doing so, she was securing her status along with the fashion powerhouse who was the 2016 aesthetic connoisseur. Under Alessandro Michele, Gucci led the fashionista enterprise away from dreary minimalism to ‘more is more,’14 sartorial excess whose boldness was a flame amongst dull flickers. Her high fashion ensemble rivals the encoded message of power that Beyoncé channeled and wielded. Perhaps this is a proclamation of Beyoncé the Businesswoman, calculated in the inconsistencies that her visage produces; we see both a radical reclamation of Black heritage, one which vehemently denies privilege to a dominant U.S. American narrative of Blackness, as well as lavish trimmings that dramatize the singer as an object to be examined, glittering sequins, embroidered embellishments, and an overlay of fabric textures that bend against her body. This but one detail of Beyoncé the Artist.

Comparing the Gucci bodysuit with the promotional video and there is disconnect between what we see and what we know. In the promotional video, Beyoncé wears an all-white outfit, each piece we examine slightly more opulent that the one we looked at before. Her jewel encrusted cowboy hat, a symbol associated with the mythic ‘cowboy hero’ of the American West, is inconsistent with her ensemble — the cowboy hat is an accoutrement, and it wouldn’t be misguided to consider her a cowboy-esque sensation. We cannot deny that Beyoncé can — and successful does — convert the signature marker of the cowboy as authority, as the policing entity that ‘conquers’ the wildness of the frontier, into an artificial, decadent illusion to dress herself up for a performance. I am not interested in her parafictional role in re-inventing “the cowboy” here, but in what this moment signals to us. She is undoubtedly beautiful, and to make the suggestion that Beyoncé is only dressing up as a fictionalized cowboy-girl hybrid, a mesmerizing spectacle that we cannot help but gaze upon and stare at, is to reduce the double entendre of her act. However, we know this outfit is not what she wears when she sings Formation.

The looped image of the GIF is the exact moment when Beyoncé walks down the stage to the opening instruments of Daddy Lessons.15 Daddy Lessons is the sixth song from Lemonade and its presence stirred analyses regarding its placement on the spectrum of “country.” Pruning these publications, news articles, opinion pieces, media chatter, and all ideas in between, Daddy Lessons posed a contentious question in terms of its genre residency. Did it qualify as country? What were its qualifications? If Daddy Lessons was a country song, could we present Beyoncé as a quasi-country artist? When, and at what moment, does something become country? And for whom did this space belong to? These queries were impassioned, and it isn’t difficult to understand why the song’s existence incensed participants to feel a particular way or the other. What became the axis from which all conversation alluded to was the dilemma of origin. Country music could not be appropriated by Black folks if it had been stolen from them by white artists first; simultaneously, it seemed unthinkable that Beyoncé the Superstar could saunter into country music without having the time or credentials to ‘belong’ in that space.

The debates can be traced to one purpose — the reclamation of the lineage’s origins. These conversations are useful to a point; there certainly is a need for recognition of the deliberate elimination of Black creativity, innovation, and value that has formed a vital function within the infrastructure of the modern world. To deny Blackness as a source of country music is deliberate obfuscation in which we diminish contributions from human beings simply because we are concerned about the palpable effects of racialization. However, to simply re-insert Blackness into the archive is to continue to grant legitimacy and authority to the very structures and arrangement of networks that produce Blackness as antithetical to modernity and progress. This does not mean that we should deny the very real consequences that emerged from corporate interests through race records, hillbilly music, and the absence of Black artists in U.S. history.16 Rather, I find these conversations rooted in a desire for devaluation, a debasement through the penetrative conditions of power. A reshuffling of the power dynamics does not eliminate the real, tangible trauma, pain, hurt, and violence that has been inflicted upon people, and it does not reduce the affective ‘afterlife’ of living through these tragedies (here, I am thinking of David Scott’s Conscripts of Modernity and our fascination with reappropriating these historical events into pseudo-empowered and romanticized narratives of survival). Instead, Daddy Lessons reveals our obsession with the charade of origin — and how its existence resounds our fear of living through the possibilities of a something else… something we don’t explicitly have a word for quite yet.

For those unaware, Daddy Lessons wasn’t simply a contentious affair during Lemonade‘s release. Rather, Beyoncé performance at the 2016 CMA Awards, accompanied by The Chicks, became the stimulant for Cowboy Carter’s edifice. Looking at the May 1 homepage of beencountry.com, directly above the GIF of Beyoncé during the fourth act of the Houston show, is a backstage photograph of Beyoncé in between the country music trio. Beyoncé leans into Natalie with her head tilted closely to Natalie’s. Beyoncé’s facial expression is playful with puckered lips, left eye closed in a semi-wink. To Beyoncé’s right is Emily, who is smiling widely; Martie’s smile is reserved, but she raises her glass higher than Emily’s. The photograph has captured a successful toast to the quartet, who celebrate their rewarding collaboration. Following the broadcast, many voiced that the partnership was collusion — Beyoncé became the target of backlash from the CMA Awards’ creatives choice to include her in on the show’s roster. Even more pointedly, audiences bristled at the presumptive ‘cosigning’ by The Chicks, who performed alongside the singer; thirteen years later and American audiences resounded that neither of the musical acts belonged at the CMA Awards. However, they sharply voiced their thoughts online that Beyoncé did not belong because ‘she isn’t what country represents.’17

The Chicks represent a particular case where their whiteness offered no protection because their voices, for a short-lived moment, denounced what “country” represented. The musical trio were on their way to country superstardom by the late 90s, and in 2000 were quickly advancing to the top of the genre thanks to their peppy subversion of the murder ballad trope in “Goodbye Earl.”18 Goodbye Earl was an expression of survival catharsis through a beloved melodrama trope — the victim’s inevitable and ‘violent’ revenge — but it also was one representation of the girl power message in the 90s and early 2000s. Goodbye Earl wasn’t simply vindication by the abused partner, but it was a collective response that was forged by friendship. And it wasn’t simply the invulnerability of the friendship that mattered, it was recognizing that the woman’s best friend from high school devised the husband’s demise so they could be liberated and happy with one another, side by side.19 However, The Chicks were one iteration of the growing mainstream cultural capital that was embedded into the ‘girl power’ movement and the proliferation of women artists — Spice Girls to TLC to En Vogue to All Saints and Destiny’s Child. We had badass fictional women characters, like Buffy, Xena, Jessie Spano, and the quartet of friends, Khadijah, Synclaire, Regina, and Maxine from Living Single. Clarice Starling oozed a radical, soft charm that has made Silence of the Lambs one of my go-to films for comfort. There were the unique quasi-anti-establishment icons like Kat Strafford, the resilient Jackie Brown that transcends her ‘limits,’ the cool disaffected personality of Daria Morgendorffer, the fierce and passionate cross-dressing Mulan who pledges herself to a cause, the indestructible Sidney Prescott who remained a force. The Chicks were not simply a standard of country music, but they were a beloved presence for what they meant to 90s/early 2000s audiences.

However, The Chicks became a real, credible threat to the country music establishment because their candor jeopardized the legitimacy of what country music was predicated upon — America itself & America as a business. They were blackballed by the country music industry due to pressure from the American public following lead vocalist Natalie Maines’ comments on a London stage in March 2003. Maines’ offense was her proclamation signaled grievances with the geopolitical actions of the United States, and thereby questioning the nation-state’s ‘right’ to exert authority and unity outside of its borders. Maines stated, “We do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.”20 There was an outcry from radio listeners, incensed and shocked following Maines’ declaration; the words were not attributed to Maines individual, but was a collective deed inscribed to the other two members of the trio. Not only had Maines committed the egregious offense of insulting the United States, but The Chicks questioned the integrity of President Bush — and by extension, the American public, reeling from the aftermath of 9/11. And while US American identity has been tumultuous and difficult to consolidate to a unified definition, following the terrorist attack identity was fixed around the preservation of what had survived such catastrophe.

There are differences between patriotism and nationalism, but the destabilization of hegemonic, immaterial values and traditions that constitute America signaled a failure, an identity on the brink of collapse. The difficulty in interpreting American identity is its malleability, a set of symbols that are rearranged and amended to justify social structures and power dynamics. These core “values” are not static and fixed, because ultimately ideals like liberty, justice, and freedom — abstract institutions which are fiercely protected and revered — are in flux, looping through diverse representations as they are needed. Margulies states that the matrix of American identity is contingent upon values that are endlessly contested, particularly when these values are incompatible with one another, or place demands upon citizens and their society. 21 Patriotic and nationalist sentiments in American identity can converge under conditions of threat and uncertainty;22 and following 9/11, American citizens felt that there was a “perceived threat” in those who questioned federal policies that had been sent overseas to ‘liberate’ people from the tyranny of suppressive ideologies. While the ‘American Creed’ responds to elastic perils, the fear of what is believed to be at stake is magnified within the public’s imagination.23 Maines’ reactionary comment was not unthinkable because it criticized President Bush or the invasion of Iraq, but it was a seditious perspective that threatened the American public who were directly implicated into the attack. It revealed a fissure in American unity, particularly in a moment where unity and allegiance to the people of the United States had been made powerless.

The American public rallied around the defense of America against The Chicks’ condemnation of its values — beliefs which were now being contested, challenged, and threatened at home. Radio listeners’ outcry was resolved by corporate interests; Cumulus Media, along with Clear Channel Communications and Cox Communications, were media conglomerates that held the majority of radio stations in America who encouraged local radio station directors to ban “The Chicks’ music if they felt the need to do so.”24 The alienation which fell upon The Chicks was swift and inescapable. ‘Chick Tosses’ were organized to destroy their CDs,25 Robison’s father — a teacher — began receiving hateful letters that labeled him a ‘traitor’ by association,26 metal detectors and bomb-sniffing dogs were adopted at their American concert venues, and radio DJs were fired for playing their music.27 However, their blacklisting from their home in country music was not explicitly a result of corporate policies, but a social movement from radio listeners whose political grievances needed to be addressed by radio stations.28 Despite the soft ban reversal on The Chicks, the damage had been done. The Chicks posed on the May 2, 2003 Entertainment Weekly cover, the trio nude sans for large black lettered epithets coating their bodies; phrases like “Boycott,” “Dixie sluts,” “Shut up!” and “Traitors” branded their bodies. As they faced the criticism of their comments amidst the London crowd, The Chicks were confronted by an incensed American public who flexed their power in organizing boycotts and prowar rallies.29

Beyoncé’s link to The Chick underscores a recognition of how social identities are marked antithetical or resistant to the goals of the nationalist project. Beyoncé’s ostracization from the country music industry nearly eight years ago — who refused to label her country-inflected Daddy Lessons as “country enough” — mirrors the estrangement that The Chicks felt thirteen years prior from their 2003 proclamation in London; the archival photograph, despite its convivial allure, does not betray the anguish of its legacy. As viewers stare at the women quartet, we are met with their euphoric gazes. Undoubtedly, it is a moment of triumph, a blending of genres that the CMA Awards’ attendants and viewers anticipated but were unprepared for; however, it is also a reminder of the retaliatory sanctioning that the four received in response to exposing vulnerabilities of the United States and its enterprises. In these four women, the photograph toasts their successful obfuscation to the imagined power the American public accessed within the country music establishment, but it also declares the realities of the ongoing desire that seeks to reduce and eliminate their presences.

Above the celebratory photograph of Beyoncé and The Chicks is an archival photograph, identified by an accompanying caption, “1968 – Gadsen [sp] High School, Gadsen [sp], Alabama / Mathew Knowles, Number 33.” Knowles stands sixth from the left, the singular Black basketball player photographed on the team roster. Knowles is a Gadsden native and has never been apprehensive in sharing his Alabama roots; similarly, he’s publicized the difficulties of growing up in the desegregating, deep South. In his own words, Knowles was brought up in small town living, one of six kids to integrate at Litchfield Junior High whose size ranged between 700 to 800 students.30 Following the release of Cowboy Carter, Gadsden’s residents reacted positively to their acknowledgment — and the role which the Knowles family has played in the history of Gadsden.31

But the history of Gadsden is a commemoration of ongoing loss. Appropriately, on July 4, 1845, a new city was designated ‘Gadsden’ after Colonel James Gadsden, who passed through the area, accompanying Andrew Jackson.32 Famously, Gadsden — a choice proposed by Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis — was the U.S. representative sent to negotiate with Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna on acquiring land that would provide an opportunity to build a transcontinental railroad.33 In 1904, Gadsden became the site of the industry, with the relocation of Southern Steel Company of Ensley as well as the nearly century-long residence of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company.34 Economic prosperity followed industrious boom, developing the city into a commercial hub that signaled progress. Only two years later, in 1906, Gadsden became the site of the 1906 lynching of Bunk Richardson — abducted by an angry white mob who was one of six indicted in the rape and murder of a white woman. The commemorative plaque sits beside the railroad bridge on the corner of the sidewalk; the large sign, with tiny, engraved letters refrain from publicizing the grim realities of Gadsden’s life over one hundred years ago. The plaque states,

Department of Archives and History via newspapers.com.35

In the middle of the night on February 11, 1906, a large white mob abducted Bunk Richardson from the Etowah County Jail in Gadsden and lynched him. In July 1905, three men were accused of rape and murder of a white woman. Bunk Richardson was not involved in the crime but knew one of the suspects and was also arrested. After the four were taken to the Etowah County Jail in Gadsden, a mob of 300 people gathered to lynch the suspects. The mob was successfully held back and the four prisoners were taken to Jefferson County the following day. Two of the men, Jack Hunter and Vance Garner, were later tried, convicted, and executed in Gadsden for the crime. The third, Will Johnson, was also convicted and sentenced to death, but Alabama Governor William Jelks doubted Mr. Johnson’s guilt and commuted his sentence to life in prison. Mr. Johnson was sent back to Jefferson County to serve his sentence. The commutation of Will Johnson’s sentence sparked outrage in Gadsden, and a mob responded by seizing Bunk Richardson from the jail although he had never been charged with the crime. The mob dragged Mr. Richardson down the street and hung him from the train trestles crossing over the Coosa River. Mr. Richardson’s relatives were forced to leave town and abandon thriving businesses while the entire (Black) community lived in fear. No one was ever charged for the lynching of Bunk Richardson.36

The lynching of Bunk Richardson — maintaining his innocence37 — is not unusual. His death, mapped onto Gadsden, transforms his loss of life into a melancholic reminder of inhumanity, responsive to perceived illusions of threats. The loss of Richardson, one of many lynching victims, reveals the banal brutality of Southern racial violence. Richardson epitomizes how lynching served as a grotesque ritual of white masculine performance,38 a calculated spectacle designed to reinforce and terrorize, transforming murder into a perverse affirmation of racial hierarchy. Collective violence emerges as a calculated mechanism to suppress Black autonomy, revealing the United States’ fundamental resistance to extending humanity beyond its extractive racial logics. The nation’s foundational architecture is constructed through traumatic acts of oppression — each violent intervention a deliberate strategy to maintain hierarchical boundaries and to quell the skepticism of the rationale of subjection. Consider, for instance, the deliberate marking of Mathew Knowles as the sole Black basketball player from Gadsden, Alabama, a space saturated with the legacy of lynching, which epitomizes how white supremacist violence meticulously circumscribes and constraints Black potential. In this context, Beyoncé’s visual proclamation within beencountry.com, linking her father’s origins with The Chicks and herself, becomes a cartography of resistance — a reimagining of space beyond its violent inscriptions. Here, we witness the announcement of Beyoncé the Black Woman, indebted to the histories that have fostered her identity, her presentation to the world, how she elects to represent herself knowingly and willingly. We also are at a site of instability, unable to reconcile ourselves with how Black bodies have been reduced to flesh, to a negative subsistence that forges the proliferation of white presence. It is meant to be both inviting and unwelcoming, an exposition of the language of suffering that is inscribed onto these bodies. Beyoncé wants us to recognize such distress, masked into moments of spectacle that are hard for us to turn away from; to keep us looking is to saturate viewers into the inconsistencies of “being” that are afforded to her.

What does it mean to be? And what occurs when this sensation “to be” is denied?

At the center of beencountry.com is an archival photograph of Linda Martell, born Thelma Bynem, taken in 1970. This was the same year that her first commercially successful song “Color Him Father” earned her the descriptive feature as the ‘first Black female solo artist to perform at the Grand Ole Opry.’39 In the photo, Martell wears a beautifully bedazzled black suit, and the collar, the long sleeves, the sides of the pants glitter with a paisley design. The image is imposed on a grainy photograph of what appears to be the union of a blue sky with the dry, hill landscape. Examining the photograph closer, we see her fingers resting along the guitar strings, as if patiently waiting for a request that she can fulfill; her body leaning against a wooden fence. It feels like we are in the midst of a serenade, catching a break in Martell’s facade in such a vulnerable moment. Her bangs obscure her face, but her smile — like Beyonce’s during the Houston show — is incandescent. Although the light reflecting from the shimmering sequins of her suit casts a soft glow, Martell’s expression radiates an elation that stirs our curiosity. For what purpose do we get to look on Martell’s joy?

To Martell’s left is a photograph of Beyoncé gesturing with her American flag-manicured nails to her t-shirt of Linda Martell; it reads Color Me Country — Linda Martell. Color Me Country is Martell’s sole album, recorded in a single twelve-hour session,40 characterized by Rolling Stone as “an alternately spunky and heart-melting honky-tonk set.” It was also the only country derived album Martell released prior to being blackballed from the industry by producer Shelby Singleton Jr.41 Linda Martell was an unexpected phenomenon, her origins as a spectacle within country music was an exploitative tactic to produce profit. Duke Rayner, credited for “discovering” Martell, was forthright in the ambitions that she could deliver, as a ‘colored girl that could sing Country and Western’ would ‘really give him something.’42 Martell could embody a novel experience that the American public could consume and possess; rather than simply be a groundbreaking pioneer for Black artists within the country music establishment, Martell was fashioned as both a fixture within a music scene in transition, but an oddity that would impair conjecture about country as a hostile, regressive space of Southern racism.43

Succinctly, Martell’s significance within country music was twofold. One, she was a promising talent who had dabbled prior in country music, so she had some experience; and two, along with O.B. McClinton and Stoney Edwards, she was emblematic of “country’s supposed racial progressivism.”44 The 1970s offered a glimmer of hope that Black musicians could not simply be profitable, but that they would emerge as success stories, a testament of radical integration following a fourteen-year civil rights campaign that championed racial equity. While Martell is a prominent example of Black women’s enmeshment to the country music genre — and partially, the country music establishment — other Black women were briefly inducted to the scene including Ruby Falls, Barbara Cooper, Lenora Ross, and Virginia Kirby.45 What is curious about the 1970s is the diametrical presumptions that country music record companies made about their Black musicians, but the failure of Black country artists themselves to reconcile their popularity as a genuine byproduct of popular audience interest. Martell’s spread in Ebony reveals that her success yields to Black country singers’ positioning constitutive of an origination to ‘Blackness’ to the genre. By insertion, Martell — along with other country music Black musicians — became an avatar for a synthesis of palatable Blackness that participated within the constraints of country music’s metrics of whiteness.

For example, in the Ebony issue, Singleton — seemingly the spokesman who shared similar convictions as other country music experts — stated that, “Rhythm and blues and country music are the most parallel types of music. It’s the working people who make up the listeners for both.”46 Interestingly, the country music enterprise during the 1970s sought to commercialize the genre to expand its appeal beyond the initial socioeconomic ‘fringes’ whom country music had indulged in prior decades. Yet, it is not surprising that the glamor of progressivism faded in the wake of profitability, particularly when Martell’s allure as a Black country artist was driven by Singleton’s initiative of ‘selling’ — Black country artists and musicians had to produce the capacity to sell.47 I do not believe that it was a coincidence that country music listeners began to grow disenchanted with its growing popularity during the 1970s, particularly as its listening base expanded to cities like New York City. The first all-country radio station in the city, WHN, gained the largest country radio audience by the end of the decade, record stores saw increasing country music sales by 75 percent and more, and local country music clubs bloomed and produced local talent.48

Martell’s temporary appeal was not simply cut short by commercial excommunication by Singleton, maddened that his rising star was seeking commercial support elsewhere, particularly amidst the surging popularity Martell’s labelmate Jeannie C. Riley. Martell’s contract sanctioned her ability to record with other companies once she had fulfilled her contract with Plantation Records, but no sooner had Singleton terminated Martell’s career with impending legal action against companies who recorded Martell.49 Rather, it derived from the growing disillusionment of country music listeners who now witnessed the genre become a twentieth-century “belle époque” trademark, seemingly stripping country music of its truisms of white rusticity, draped in the Southern imaginary of the Southern rural figure as antithetical to cosmopolitan white, upper-class elite identity that had arose post-WWII.50 Country music acolytes exploited the genre as a space which conjured an identity that would assuage their white guilt and burdens, separating themselves from the affluent white identity which had infiltrated the sanctity of their beloved, rural Southern culture that was country music. In turn, this exploited reverence became a marketing strategy that became profitability during the early twentieth-century, and record companies were acutely aware of how popular demand shaped and tooled commercial enterprises in response to those tastes.

Hubbs substantiates this fissure through the market demands of the 1920s, but also how the Jim Crow caste system helped attune the kind of representations that emerged from the radical, liberal policies of a post-Civil Rights era. Hubbs writes,

The racial and class ideology that held great institutional and scientific sway in the early twentieth century regarded poor whites and poor blacks as biologically and culturally distinct groups and regarded both groups as fundamentally distinct from middle- and upper-class whites. Musical categories and knowledge were established in accordance with these expert perspectives… […] popular music became an important tool in folklore’s project of demonstrating the natural remote ness of the folk from the civilized classes and the (putatively) inevitable distance between black and white folk cultures.51

Martell’s profound marginalization within country music and her subsequent rejection from the space does not simply reflect personal vendettas from country purveyors or a ‘whitelash’ from country music’s devoted American public who were anxious about the loss of the “authenticity” to the genre’s presumed roots, fixed into the Southern provincial reverie. Rather, country music was typified — and continues to be — as an active site where ideologies of exclusion were muddied by an interconnection of racist and classist conventions, delineated by ‘scientific’ prescriptions. The displacement of Martell, and other Black musicians, illustrates the melancholy of identities that are forged by structures which were devised to exclude and dehumanize. Beyoncé renders a hypervisibility to Martell’s experiences within country music; as a Black country pioneer and woman, Martell is distinct in reminding viewers of the way she becomes identifiable to us through the commodity spectacle that she represented for Black musical contribution in a space that deliberately marked her as out of place. Simultaneously, we see Martell as remarkably absent, invisible in terms of what just her historical presence represents; Martell becomes a mechanism that reveals the failures of institutional support, an identity deliberately bound by social processes that have deprived her of recognition on the merits of her accomplishments — rather, we see what she could not accomplish that makes her so dazzling to see.

This is a moment of dis-possession. This is where those perceived differences trace minoritarian bodies and subjecthood, an identity of denial but an ongoing glimmer for the potentiality to shed those deterrents. Perhaps not today, but someday. The ongoing dispossession that Beyoncé points out is a core value for beencountry.com, but I believe it becomes the most distinguishable on this update.

I have not yet talked about the significance of the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit as I believe that is a monographic quality that underpins Act II: Cowboy Carter. I will save that discussion for a later day, as this piece wound up being much more labored than I had anticipated it to be. Ideally, I would like to discuss some of the aesthetic choices that dictated the visual direction for this album — namely, the waving billboard from the Cowboy Carter teaser & the recently released Cowboy Carter holiday card set — but that will be for another day.

I will return once I churn out my prospectus’ previous literature section (which is killing me btw). If I am not back before then — happy holidays!

Notes

- Author is in fact not surprised. This is me being insincere. ↩︎

- I haven’t had an opportunity to include this publication in any of my writing and I am THRILLED that Bey is the reason I get to belabor it. ↩︎

- When I talk about “empire” and “imperial” processes in relation to the United States, I am deliberately referencing the early formations of the American nation-state of the nineteenth-century — such as the “grooming” of the American West; the dispossession of Indigenous communities and its people via broken treaties and promises, the construction of an essentialist classification system via the Dawes Rolls; enslavement of Black people as economic puppets; marked absences of Chinese immigrant laborers along the railroad systems; the “giants” of industry of the Gilded Age that enacted fee-based governances; and manipulation of foreign affairs and investment opportunities that props up the U.S. as a “sole” economic powerhouse. ↩︎

- Lester Fabian Brathwaite, “Beyoncé drops new music following Verizon Super Bowl ad, announces Renaissance: Act II,” Entertainment Weekly, updated February 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Kelsey McKinney, “New albums will come out on Fridays instead of Tuesdays now. Blame Beyonce.” Vox, February 26, 2015. McKinney’s title also raises an eyebrow because of its tonal prejudice — why not simply say “Beyonce is responsible” instead? Naming the responsibility as blame constructs an unfair criticism toward the musical artist who isn’t dictating the standardization of musical releases.

McKinney writes in the article that its really ‘piracy’ that is the impetus for the new global standard, but it’s not lost that partly the writer is incensed at Beyoncé for ‘dismantling’ release tradition, rather than shifting this as a problem with an industry that does not value ‘artistry,’ but the dollar signs attached to a commodity. ↩︎ - “Beyoncé on Her Alter Ego, Sasha Fierce,” from The Oprah Winfrey Show, 2008. Uploaded on August 17, 2019. ↩︎

- Jason Eppink, “A brief history of the GIF (so far),” Journal of Visual Culture 13, no. 3 (December 2014): 301. ↩︎

- Eppink, “A brief history of the GIF (so far),” 303. ↩︎

- In particular, these texts are Diana Taylor’s The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (2003) and Karen Roybal’s Archives of Dispossession: Recovering the Testimonios of Mexican American Herederas, 1848-1960 (2017). Taylor’s work is what drove me away from a strictly art historical perspective into an amalgamated interdisciplinary approach — like art history, art practice, and performance studies. And Roybal’s research does a good job to explore the material effects that colonization and territorial expansion had upon Mexican American women (it has its limitations; nonetheless, it is an intervention into the formation of US hegemony and imperial movements). ↩︎

- I really hate the word ‘alternative’ because it is replete with logocentric ideals of the Global North (the West). Unfortunately, language has no suitable ‘substitutions’ quite yet that can replace this term without the continued privileging of Global North/West epistemologies. ↩︎

- Before the grotesque inflation of ticket prices, I was fortunate to grab tickets to the May 12th date. When people say Beyoncé is an experience — believe them. I have only ever had a total of three out-of-body ephemeral experiences at live shows, though I did enjoy many different musical events in my lifetime. Bey was one; the second, Lady Gaga’s Monster Ball at the Staples Center in 2010; and three, Nekrogoblikon at the House of Blues in May 2022. Nekro were the opening act for GWAR, but literally didn’t care (and still don’t) for them. These are memories I hope to someday impart on my annoyed grandchildren (or grand fur-babies!). ↩︎

- Beyoncé, “BTS: The Formation World Tour (Houston),” YouTube, September 22, 2016, 01:09. ↩︎

- Ashon T. Crawley, Black Pentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 6. ↩︎

- Jill Manoff, “How Gucci ruled 2016,” Glossy, December 5, 2016. ↩︎

- Joshua Ramon, “Beyonce Daddy Lessons Formation Tour Houston Texas,” by joshuaramon6719, YouTube, 24 sec. I am incredibly thankful for Joshua Ramon on YouTube for catching what seemed to be the only clip of Daddy Lessons from The Formation Tour. I am also very surprised my sleuthing paid off! ↩︎

- For further information about race records, ‘origins’ of Black-made musical genres, see William G. Roy’s “Race records” and “hillbilly music”: institutional origins of racial categories in the American commercial recording industry, David Robertson’s W.C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues, Allan Sutton’s Race Records and the American Recording Industry, 1919-1945, Paul Oliver’s Songsters and Saints: Vocal Traditions on Race Records, Samuel Charters’ The Country Blues, Robert Palmer’s Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta, and Elijah Wald’s Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of Blues. ↩︎

- Joe Coscarelli, “Beyoncé’s C.M.A. Awards Performance Becomes the Target of Backlash,” The New York Times, November 3, 2016. ↩︎

- I recently introduced my husband to this song and explained the oral history of The Chicks, which was a huge incentive for undertaking this update as the first exploration of beencountry.com. But mostly, Goodbye Earl was the jam on my CD player at the time. ↩︎

- We could certainly make the argument that, much like Dolly Parton’s “Jolene,” Goodbye Earl has some sapphic undertones buried within it. Perhaps another day? ↩︎

- Steve Knopper, “An Oral History of The Chicks’ Seismic 2003 Controversy From the Industry Execs Who Lived It,” Billboard, June 14, 2022. ↩︎

- Joseph Margulies, What Changed When Everything Changed: 9/11 and the Making of National Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 27. ↩︎

- Qiong Li and Marilynn B. Brewer, “What Does It Mean to Be an American? Patriotism, Nationalism, and American Identity after 9/11,” Political Psychology 25, no. 5 (October 2004): 736-737. ↩︎

- Margulies, What Changed When Everything Changed, 61. ↩︎

- Randy Rudder, “In Whose Name? Country Artists Speak Out on Gulf War II,” in Country Music Goes to War, eds. Charles K. Wolfe and James E. Akenson (Lexington: University of Press of Kentucky, 2005), 214. ↩︎

- Billboard, “Protesters Destroy Dixie Chick CDs,” Billboard, March 17, 2003; Jada Watson and Lori Burns, “Resisting exile and asserting musical voice: the Dixie Chicks are ‘Not Ready to Make Nice’,” Popular Music 29, no. 3 (2010): 328. ↩︎

- Rudder, “In Whose Name?,”214. ↩︎

- Watson and Burns, “Resisting exile,” 328. ↩︎

- Gabriel Rossman, “THE DIXIE CHICKS RADIO BOYCOTT,” in Climbing the Charts: What Radio Airplay Tells Us about the Diffusion of Innovation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 65, 67. ↩︎

- William Hart, “The Country Connection: Country Music, 9/11, and the War on Terrorism,” in The Selling of 9/11: How a National Tragedy Became a Commodity, ed. Dana Heller (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 162. ↩︎

- #TeamEBONY, “EXCLUSIVE: Mathew Knowles Says Internalized Colorism Led Him to Tina Knowles Lawson,” Ebony, February 2, 2018. ↩︎

- Greg Bailey, “Beyonce gives shoutout to Gadsden on ‘Cowboy Carter’ album,” The Gadsden Times, April 2, 2024. ↩︎

- “Gadsden, Alabama,” The Historical Marker Database, updated on September 29, 2020. ↩︎

- NCC Staff, “The Gadsden Purchase and a failed attempt at a southern railroad,” National Constitution Center, December 30, 2022; Office of the Historian, “Milestones: 1830-1860 — Gadsden Purchase, 1853-1854,” Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, accessed 2024. ↩︎

- “Gadsden, Alabama.” ↩︎

- If this news clipping is too heavy, hurtful, and is requested to be taken down, I will do so immediately. Side note: this was a tough section to write about. I feel profound sadness deep within when I dig through archival records such as these — and no, it doesn’t get easier the more you’re exposed to it. ↩︎

- Donna Thorton, “5 places in Gadsden, Alabama where civil rights history was made,” The Gadsden Times, updated February 10, 2022. Emphasis my own. ↩︎

- This deliberate restraint in detailing Bunk Richardson’s murder stems from an ethical imperative: to refuse white supremacist violence the spectacle of its own brutality. The abstraction is not an erasure, but a radical act of resistance — denying the perpetrators the perverse satisfaction of sensationalized recounting while centering the humanity violently stolen from Bunk Richardson on February 11, 1906. ↩︎

- Kristina DuRocher, Raising Racists: The Socialization of White Children in Jim Crow South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011), chap. 5. ↩︎

- Briannah Rivera, “Everything to Know About Linda Martell,” Elle Magazine, published April 2, 2024. ↩︎

- Rivera, “Everything to Know About Linda Martell.” ↩︎

- David Browne, “Linda Martell: Country Music’s Lost Pioneer,” Rolling Stone Magazine, published September 2, 2020. ↩︎

- Diane Pecknold, “Negotiating Gender, Race, and Class in Post–Civil Rights Country Music: How Linda Martell and Jeannie C. Riley Stormed the Plantation,” in Country Boys and Redneck Women: New Essays in Gender and Country Music (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 148. ↩︎

- Pecknold, “Negotiating Gender, Race, and Class,” 149. ↩︎

- Charles L. Hughes, “”I’m the Other One”: O.B. McClinton and the Racial Politics of Country Music in the 1970s,” in The Honky Tonk on the Left: Progressive Thought in Country Music (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018), 122. ↩︎

- Amanda Marie Martinez, “Redneck Chic: Race and the Country Music Industry in the 1970s,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32, no. 2 (June 2020): 135. ↩︎

- Ebony, “Country Music Gets Soul,” Ebony, March 1970, p.70. ↩︎

- Tyler Mahan Coe, “CR007 – Harper Valley PTA, Part 1: Shelby S. Singleton,” Cocaine & Rhinestones, podcast, season 1. ↩︎

- Martinez, “Redneck Chic,” 131. ↩︎

- Browne, “Linda Martell.” ↩︎

- Martinez, “Redneck Chic,” 133-134. ↩︎

- Nadine Hubbs, Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music (University of California Press: Berkeley, 2014), 69, 72. ↩︎

Leave a comment