One of the largest challenges to my writing practice is that I have mental arrows that point in disparate directions that I find it difficult to pinpoint a “place” to start. There are about five drafts sitting in my posts (yes, I have ~40% of my first elaboration on beencountry.com started!), and the largest critique of my writing for the last six years has been that I have so much that needs to be said that it is impossible to wrangle the analyses in. When I brainstorm ideas out loud, I can see the look on my husband’s face; he already knows what I am going to ask and I hear it every single time from him – “it makes sense, write it all down.”1 The crux of the dilemma at hand: having so much to say but overthinking what will make a ‘good enough’ launch into the discussion that is moving at lightning speed in my mind.

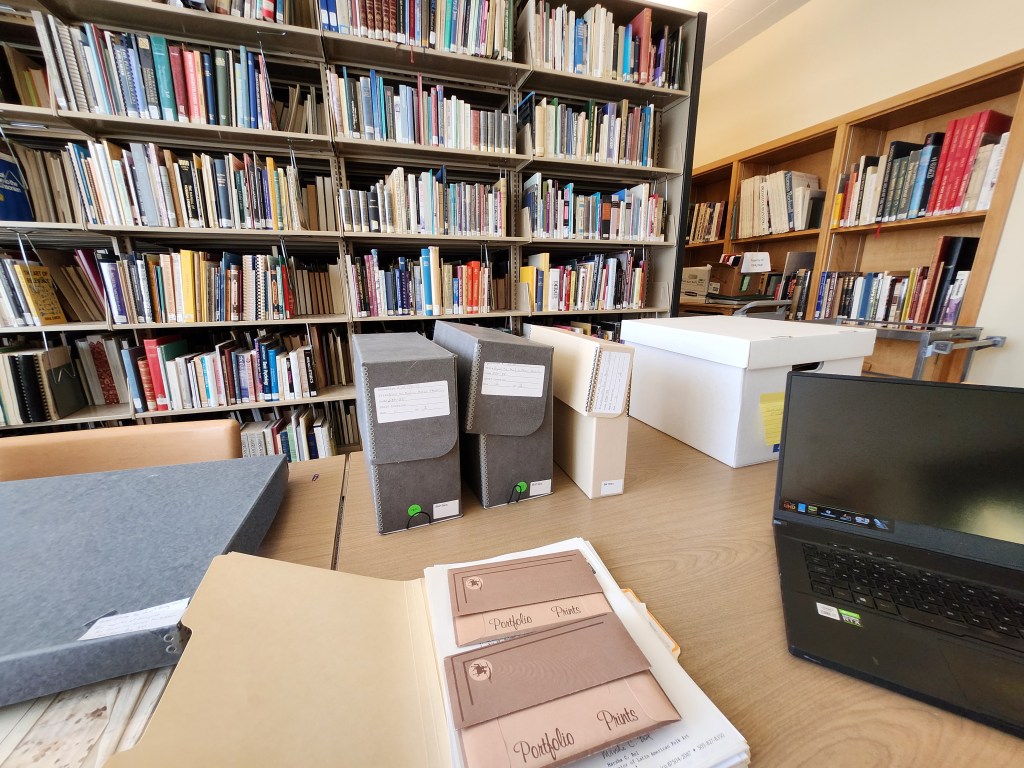

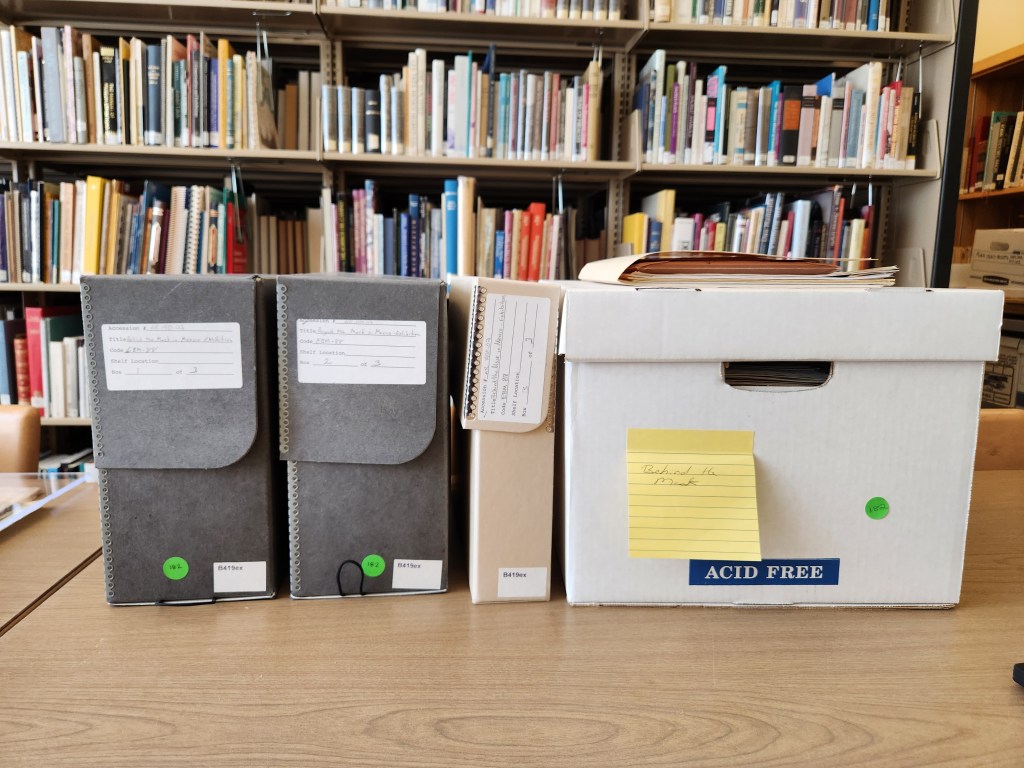

As mentioned before, I went on a workcation last month. Every other year I manage to find the desire to leave Southern California and travel someplace else; this year I settled on New Mexico because there was a way I could revisit one of my favorite museums and do some archive research. It made me think about something that I have worked through or considered within the last three years: the role of knowledge and its production, circulation, and reception to a general public/audience. One professor proposed a question that still lingers, years later.

“Could we facilitate institutions that do not become tools of colonialism?”

There is no shortage of literature about decolonizing institutions – in particular, de-colonizing museums and the role that they play within their respective societies and in the operating system of a nation-state. I have thought a lot about the role of distinguishing between affix modifiers in language, particularly regarding colonization & the legacies of imperial strategies and its tools. I run the risk of redirecting the purpose here, but it makes me ask myself and others as I continue my PhD journey: can we genuinely live in a post- or de-2 formulated world and environment? Naturally, decolonization means something entirely different, respective to the conditions of the peoples and communities impacted by different nation-states and its institutions; what it means to “de-” colonize within my world might be unsuited for someone else outside of my community, even perhaps an individual within that same “diaspora.”3

One example of the insidious ways that colonized thought continues to be perpetuated is the development and construction of the “No sabo kid” and the way it’s become a means to develop internal hierarchies between U.S. Latino people. Sure, we can poke fun at children who can hardly hold a conversation with their grandparents who live in X Latin American country who do not understand English… but for what purpose? I grew up speaking Spanish and English with equal frequency. My paternal grandmother, from El Salvador, lived in the United States and understood English quite well; however, growing up she simply refused to speak English to us… “qué? no te entiendo.” was quite a familiar refrain when we visited her every summer in Houston. I spoke Spanish on and off during my teenage years long after she had passed away and I am fortunate that I can switch between languages to speak to family. But what is hurtful to see is how others’ inability to speak the language has become weaponized by other community members (my younger siblings, for example, don’t speak Spanish but can understand it moderately well), to see how the Latine/x/a/o community is fraught with a social structure that cycles rhetoric that mimics white supremacist logic.

Certainly, I had the “advantage” of having spoken both English and Spanish in my adolescence, but it came at a cost. I was raked over the coals in elementary for not speaking English well enough, so Spanish was buried deep inside of me; I had to reteach myself, starting in junior high, how to remember the differences between estar & ser. You get to watch stupid scenes, like Orange is the New Black where a character is shamed for falling short to the Spanish-speaking white girl4 that are derogatory to the experiences of the U.S.-born Latine/x/a/o children who grew up being informed that assimilation was the only means of survival here. And it makes me think about Ariana Brown’s poem “Dear White Girls in my Spanish Class”,

So I am here, in yet another Spanish class, desperately reaching for language I hope will choose me back someday. What is it like to be a tourist in the halls of my shame? … How does it feel to take a foreign language for fun? To owe your history nothing?

The figure of the “No sabo kid” is not simply derogatory, meant to be shameful or disparaging to the shortcomings of that individual. Rather, it is a deliberate mechanism that is weaponized, exposing the vulnerabilities that render someone an “inauthentic” Latino, betraying ancestors and our mutual histories for a kind of imagined legitimacy and purity. For whose good is that for? I am uncertain if betrayal is a strong enough word for what this conversation produces because the “No sabo” dialogue often leaves a terrible impression on me whenever it crops up; it certainly seems like ‘solidarity’ doesn’t matter if one can advance themselves in an individualistic social system at the expense of others, to be perceived as an “authentic Latino” and therefore a credible/legitimate human being, despite the shared traumatic histories that underpin our individual identities.

And it makes me think about all of these subtleties in the everyday, and for who or what is de-colonized? Frankly, I am in the camp that such a future is impossible; de-colonization cannot unwind the ways that our identities and the processes that have formed our subjectivity have become tethered to these histories and processes. David Scott’s work is invested in asking us to conceptualize how the dimensions of colonialism have actively and continue to impact conditions of existence and being; coloniality as a condition has shaped present-day structures, from surveillance to unnecessary romanticization of the past to agency and its production via power. In Conscripts of Modernity, Scott alludes to a need to advance narratives which acknowledge the problems and tragic circumstances, rather than simply entrap anti-colonial events as points of “resistance” and heroic valor.

In chapter two, he states,

“And therefore my concern is to suggest how picturing colonialism in one way—as a system of totalizing degradation—enables (indeed obliges) the critical response to it to take the form of the longing for anticolonial overcoming or revolution. Consequently, my argument is that insofar as we formulate our historical discontent around the picture of colonial slavery as degradation and dehumanization there is no way out of that Romantic (and vindicationist) language-game of revolutionary overcoming and rehumanization that supports and sustains it.”

Scott brings forward the notion that we cannot absolve the conditions that have led our “world” – here, I mean to a globalized, interlinked and connected world – by trying to rewrite the consequences or negative effects into optimistic, idealized versions. By framing these actions in a chronological/linear path, there is an increasing risk to not simply romanticize the actualities of these traumatic and violent events, but also to imagine that someday ‘progress’ will lead to an overcoming of such damages and consequences from that trauma. Often, when it comes to the concept of “de-colonization,” we might be led to believe that there is an eventuality where we could move beyond and undo the effects that these historical events have imprinted onto us – people, communities, relationality between those peoples, etc. Scott suggests that in attempting to recoup the losses from colonialism, we lose sight of how the legacy of colonialism will remain present in any kind of future that we develop. Certainly, this does not mean we lose sight of the past and how it has shaped our present-day conditions, but it means that we do not focus upon fetishizing these historical events so much so that we try to imagine “progress” in the future as needing to return to a pre-modern, pre-colonial past that we have perceived to be without blemish. Rather, we cannot go back – we have to live in the tragedies of colonialism, imperialism, colonization, terror, pain, betrayal.

It makes me consider what the material conditions are of an institution that holds and distributes such knowledge. I return back to my initial dilemma: could we facilitate institutions that do not become tools of colonialism?

Could we create museums to be a structure that does not reproduce ideologies that veer to cultural essentialism? Can we re-imagine these institutions as not wielding authority or supremacy, as well as becoming spaces that do not objectify or fetishize the knowledge it circulates to its public?

A side note: back in July 2022, I visited the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture a month after it opened. A month later, I was very excited for this museum because it was an instance where I felt “seen” and was excited to share this experience with my then-boyfriend, now husband; we are both from Latino families, grew up in Southern California, had similar socioeconomic upbringings, and always enthusiastic to support expressions that visualize or attempt to cultivate those sensations and experiences of growing up in the in-between world we did. I rarely take photos when I go to museums – unless it is a temporary exhibit that I would like to look at the works again – and we both were thrilled to see visual works that represented childhood memories that fade in and out of our minds. Sitting in front of Hernández’s pieces from the Juarez series was like feeling the sadness of how border-crossing for work and the survival of one’s family can incur violence and loss in multitudinous ways, Una Tarde en Meoqui brought on a conversation reminiscing of family dinners, the aroma of fresh tortillas and sopita, maybe some meat if we could afford it, where it was a special moment when both parents could be fully present; seeing the contrast of the vibrant atmosphere with the criminalization of the community’s vendors in The Arrest of the Palateros was something we saw happen, time and time again, in our own neighborhoods, even as we grew up worlds apart (I grew up in LA County, he grew up in San Bernardino County).

I think the collection does a good job of not simply telling the narratives of encoded memories that take us back to the instability of our childhood and its optimism at the brief glimmers of “good” moments (like having McDonald’s money or getting an extra quarter from grandma for doing Saturday morning chores), but allowing us to feel and recognize the importance and burden these markers have on how we elect to represent and identity ourselves. I used to be embarrassed when I would return for a new school year with only one new outfit, sometimes it was just a new pair of shoes because the other pair were “starting to talk.” I felt so ashamed when I stayed the night at my elementary school best friend’s house, and she called me ‘poor’ for the first time. I was guilty when my grandma would call, and I would pretend I had lost my voice because I just didn’t want to talk in Spanish. But seeing the visual works at the Cheech Marin Center offered the complexities of these experiences, an encounter with representations in an ‘official’ setting that not simply displayed but legitimized these problems of growing up in a particular community as valid to be made visible and seen. We hold conversations about how vital that museum visit was, because its affective quality had been realized through both of us to share and exchange the realities of our upbringings – we saw that these were widespread understandings, an intimate portrayal of things that we had internalized as kids.

This is controversial but that intimacy felt violated when we recognized some of the individuals that were circling in the space, listening to conversations that felt vulgar and disconnected from the material on display. Museums are for anyone, but not for everyone. It felt like these sensations and experiences were being gawked at because, naturally, not everyone in the audience who consumes the works will not simply engage in good faith, but simply do not have exposure to those occurrences. This isn’t to say that people should not consume or involve themselves in these material objects because they cannot relate, but it would be disingenuous to propose that there isn’t inequity in the reception of these works because of these personal differences and ideologies of society. It felt icky to hear the laughter or the indifference to these visual works because they didn’t “get it.”

It’s something I am quite familiar with in the art world, something you hear often when people are annoyed that a visual object’s labor is comparatively at odds with other materials that are displayed beside and alongside it, or the labor to produce that object is incomparable to what a viewer perceives to be ‘qualified’ to occupy space in the gallery/museum. It’s a common critique lobbed at abstract expressionism and subsequent stylistic departures – i.e., minimalism, pop art, conceptualism, etc. These become value judgments, and part of what I do not resonate with in the museum setting is that there is a difference in the anticipation of what the institution is meant to re-present and what the audience can meaningfully, in good faith, engage with. It also becomes a dilemma when the museum, as an institution within a specific nation-state, exists as a contradiction; on one hand, they are one component of a system that produces value for a public, as a commodity for the hegemonic structure, but on the other hand, the museum is a placeholder for preserved, fragmented materials that retain an air of inaccessible elitism and subsequently imagined as incompatible with the “good” of the public.

Museums have been deemed to be “spaces of education” and “places of facilitating learning” but it still seems to make us ask, for who or what are we doing these things? Can we place distance between the notion of the museum as a location of reproducing imprints of colonialism (i.e., classism) or do we need to rethink and scrap the entirety of ‘museums’ in their present-transitional nature altogether?

I don’t know where I was necessarily going with this altogether. However, a chapter in my dissertation revolves around the concept of archiving, digitizing, and the role of these practices within the framework of neoliberal ethics; namely, to think about the impossibility of eradicating the consequences of these institutions – despite their transitioning to new efforts of equity and accessibility – and how we might begin to move beyond the ‘fossilization’ that happens to specific communities, cultures, and groups of people. I should probably get to both Chambers-Letson and Muñoz’s works in the meantime, because I want to be optimistic that “something else, something more” is on the horizon.

We’re moving to what I call the “afterlife of the post- post-reality.” We go into not simply thinking about these tragedies of modernity – the slave ship, revolutions, displacement of Indigenous peoples, the plantation system, Sinophobia, xenophobia, walls and borderlands – but we begin to think about the hybridity of how they shape our impending future. I take forward that sense of (un)belonging as a commonality that these pains, these sacrifices, these losses, the pain, the suffering, the triumphs, the reconciliation… can take us to something else.

Hopefully in my next post5 I can get into Beyoncé; I have my fingers crossed that I can find a frame that is large enough to fit the collectable poster (I truly, wholly love the poster image – it was a huge component of my most recent paper, and I want to dissect it more).

Until then.

X, D.

Notes

- Other consultations that I receive while writing are nonverbally communicated; a special thank you to my four little furry babies that simply lay beside me as I talk to myself. ↩︎

- This evolved from the following two publications: Kwame Anthony Appiah, “Is the Post- in Postmodernism the Post- in Postcolonial?” (1991) and Shu-mei Shih, “Is the Post- in Postsocialism the Post- in Posthumanism?” (2012)

↩︎ - I am still not fond of the term “diaspora” or “diasporic” because it still seems inadequate to capture the relationships and intimacies that people form with specific places, environments, landscapes, or ‘worlds’ that they have not fully experienced or endured themselves. This probably has a lot to do with being the child of immigrants and the experiences I have with my parents’ native countries and thinking through the dissent that occurs within Latine/x/a/o communities. Maybe someday I’ll belabor this term – stay tuned. ↩︎

- I have no further comments about this show because I stopped watching it at this moment. ↩︎

- No, this post did not go in the direction that I initially thought it would — as usual. ↩︎

Leave a comment