When Beyoncé announced Cowboy Carter during the Super Bowl this year, I was shook — the kind of absolutely flabbergasted, stunned, “don’t play with me” type when the singles dropped. I’ll preface this writing by two things; the first, I’m not one who follows the country genre as closely as others, the second, that it took me weeks to challenge myself to get hooked by Renaissance. This doesn’t mean I’m not a Bey stan; I was fortunate to grow up in the 90s during a period where “girl power” was a kind of bubbly, quasi-empowered, vivacious, but lightwork confrontation that I needed as a kid. For younger me, it was something else to grow up with visual encounters and instances of women committed to presenting various inflections of womanhood and femininity that was formative for an identity that I so desperately wanted to possess as a child.

And yes, while Spice Girls had me obsessively buying Chupa Chups and cheering on an anthem of positivity, Destiny’s Child was a model of the fierce, in-your-face bravado that defined the kind of relationships I wanted to have with boys (shallow, but I was eight when DC really came on the map!). I didn’t really understand it then as much as I do now, but Destiny’s Child and Beyoncé cultivated a cultural geography that maps the interactions that – as a Latina – I have with myself, others, and society at large; I believe Destiny’s Child, along with Spice Girls, TLC, Exposé, and other women-centered musical acts I was exposed to as a kid (shout out to my dad, whose eclectic music from his DJing days with my mom in 1980’s LA has been the backbone of my “taste”) provided a stable framework of a process of identity that have provided at times wavering, but quite durable confidence of who I elect to present myself as and be. Certainly, I could say plenty about the lasting power of the manufacturing in the 90s of a commodified feminism, the evolutionary “progress” of how girl bands and pop acts have paved a path to contemporary dilemmas that are at stake within feminist theory and its unfolding discourse.

However, I want to return to the kind of magnetism that Beyoncé is for me all of these years later. I share the same sentiment as Kendrick — honorary Beyhive — and the last few months of sitting with Cowboy Carter has lingered with me in a way that other musical and sonic works haven’t. I’ve obsessed over this album to so many people — mom, siblings, friends, husband. Just what is it about the aura of Bey and Cowboy Carter that has me hooked five months later?

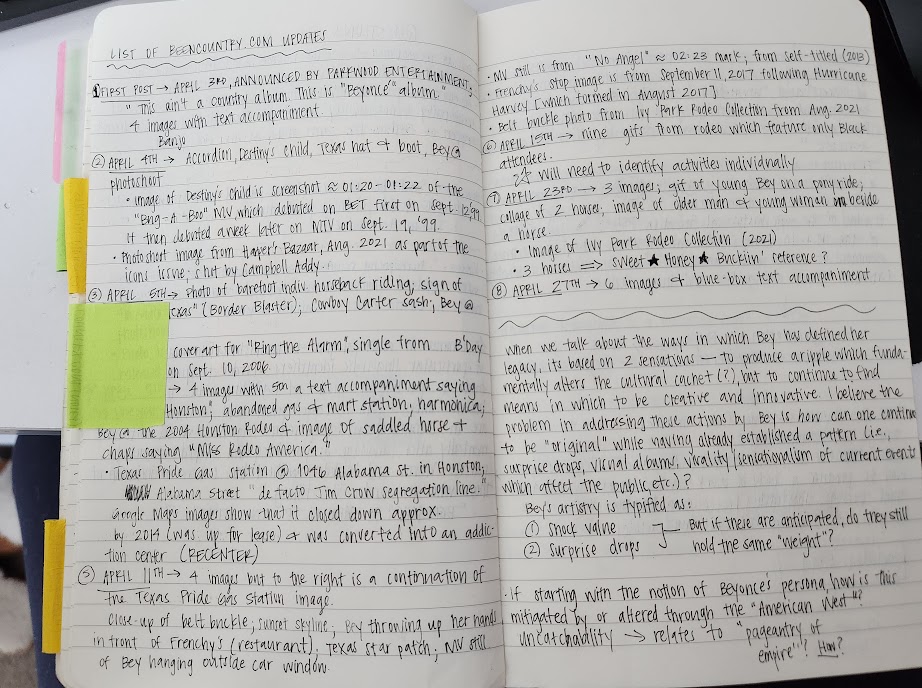

I recently wrote an extensive exploration of the initial visuals released for Cowboy Carter — a paper titled “The Rhetoric of Cowboy Carter – The Flickering and Production of Everyday Pageantry for the Minoritarian Subject.”1 In my examination, I focused explicitly on thinking through select few visuals that Beyoncé released for her eighth studio album:

- Two of the promotional images from Cowboy Carter — one & two, courtesy of Beyonce Online.org, but I culled the images in my writing from Beyonce’s official website (which you can visit here).

- act ii teaser trailer

- 16 CARRIAGES visualizer

- TEXAS HOLD ‘EM visualizer

The writing was a way for me to kind of digest the unique relationship that Beyoncé has when it comes to her music drops and the visual accompaniments she curates to join the release. It was also a selfish endeavor, masked as an academic enterprise, because who doesn’t want to make their obsession as an official, legitimate avenue of critique? There is so much discourse on Bey; I’m just another tab in an ever-growing compilation of individuals who are fascinated by her artistic process, but also converting her to an object of study. And I’m keenly aware of what that observation signals — it makes me think of Spillers’ work and the real risks that come attached to discussing Black bodies, particularly Black women bodies and the relationships that emerge from distinguishing between who is imagined possessing a body vs. who is reduced to fleshiness. My earliest encounters with Cowboy Carter were with the cover art; I had every intention of framing it as the primary object of my analysis and thinking through the critiques and responses that emerged out of her decision to make a country2 album. I also just wanted to talk about how incredible I found the final cover art to be; it was totally what I expected a Beyoncé album cover to be, but I also didn’t anticipate it because Beyoncé always seems to find nuances in order to keep us hooked.

After the album was released, I finally felt some of the sensations of what it meant to be a die-hard, hit the ground running, Beyhive affiliate. I’d recently received the worst confirmation that a core member of my favorite band had departed, so it wasn’t really surprising that I threw myself into the fantasies that Beyoncé was drawing up for her audience. And after having sat with Renaissance, seeing the kind of afterlife that it had and continues to have for fans, I was eager to write against whatever it was that Bey dropped. If the fans were right, Bey was going to drop visuals; if she didn’t drop visuals, I would write with the anticipation that she might give us more hints along the way as she rode out the album release. Every day I checked social media platforms — or at least the ones that I had access to. P.S. shout out to the Beyoncé community on Reddit… literally one of the best spaces I have ever been allowed to “exist” on. I was so anxious that Bey was going to release something overnight, that I would blink and be left behind amidst shimmering images and beautiful aesthetics that would overwhelm my senses. Even my husband was diligent in spit balling ideas with me at this point – he always provided insight to a kind of casualness in seeing and witnessing what Beyoncé did that I definitely knew I would never have the power to do again.

All of my notes were long-winded, drawn out, and run-on sentences. I was thinking about the obvious nods to rodeo pageantry in the cover art and asking questions about the relationship that the rodeo had with a beauty pageant; what kind of goals and outcomes are produced when Beyoncé elects herself as a “candidate” of such an event. I thought about the role of the “black cowboy” and what the significance is of racializing such a signifier — why is it important for us, as viewers, as an audience, as a society, communities of people, to acknowledge the role that Blackness plays within the narratives of cowboys? Cowboy Carter invoked key historical and artistic renderings – not simply rodeo imagery as a product of the construction of what America is, but thinking about the mythohistorical imaginings of Manifest Destiny and its anthropomorphizing (i.e., Gast’s “American Progress” and even some of the environments produced in paintings by Albert Bierstadt).

A lot of what I was thinking through in exploring Cowboy Carter and some of the initial impressions and responses to its debut boiled down to things like essentialism — something I’d encountered plenty, at the root of a lot of Indigenous scholarship. It wasn’t just a matter of asking “Is this album country?” or “Can country be challenged?” but querying the notion of what exactly was Beyoncé challenging for people? Lots of people took it as a personal dig, and I learned that country music is meant to come from a “place of hurt.” But what exactly is being hurt? What kind of pain is Beyoncé culpable of as a Black woman who has already been denied and excluded from? I catalogued select responses that made me go Confused Nick Young.png, especially John Schneider’s comparison of Beyoncé’s announcement of Cowboy Carter as that of a dog “make their mark.” Conversations swirled around the artist disrupting the purity of country music3… which has a history of several different subgenres, but in which its fundamental elements were anti-authority and pro-labor. It’s no surprise that those who are insulated to a specific belief of what country is are under the belief that their fringe subculture existence is rife and replete with sentiments that align with nationalist values that reflect a large swath of individuals in the U.S.? I could go further but… it’s really obvious that Beyoncé was poking at something powerful and uncomfortable.

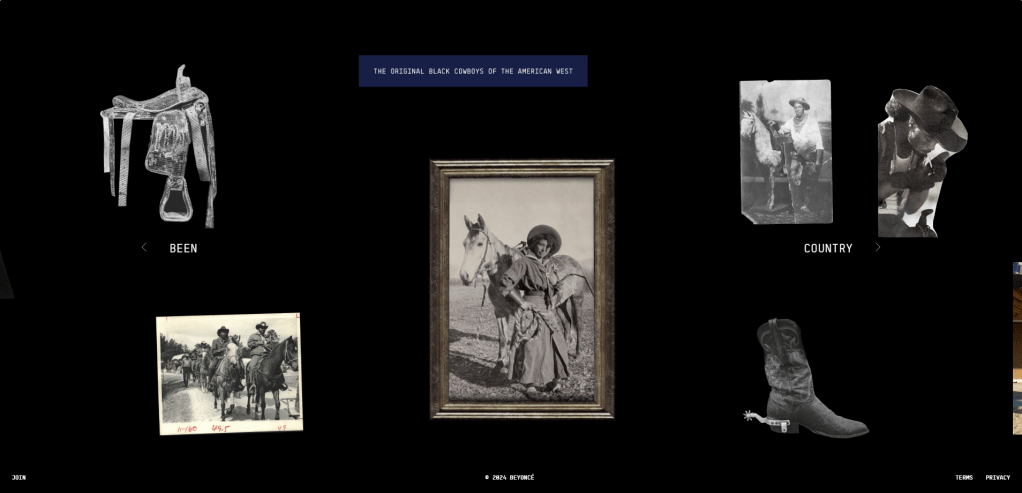

Ultimately, I don’t disagree with the narrative that part of what Beyoncé was attempting to highlight with Cowboy Carter is absences of Black people and their contributions when we revisit history and work with archival objects. It is meant to make us ask questions about what happens when we re-insert these palpable and obvious absent things back into the lineage of American history. For plenty of people, it’s incredibly important and significant to simply be seen — something that doesn’t necessarily happen for individuals who come from marginalized, disenfranchised, and underrepresented communities and experiences. It means something for me to be able to think about the kind of legacies that Beyoncé is asking us to confront and challenge; there is a sense of melancholy, a sadness that remains with us, when we think about the manners in which specific bodies and groups of individuals have been made to feel unseen, unwelcome, neglected, invisible, and unwanted.

Beyoncé — in how I thought about what Cowboy Carter was beginning to mean for me and the relationship I experienced with it — was signaling to developing a language and understanding of writing histories for herself, for others who resonated with her experiences and those feelings, to these antecedents. And yes, part of what it was is the recovery of an archive, a history, ancestors and predecessors to help shape a new legacy and path for thinking about Blackness in the “origins” of the U.S. beyond mere enslavement and the tragedies of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. It was also about contributions of Mexicans, the borderlands, Indigenous peoples, communities who were displaced and ignored, and turning these experiences and memories into fundamental parts of being woven into the fabric of the ‘beginnings’ of an empire that been built upon the flesh of “beings” to advance the nation-state.

Much like what Renaissance signaled for LGBTQIA2S+ folx and peoples, Cowboy Carter was a confrontation with a specter that Beyoncé wanted us to see as an ancestor; it was a veneration, a remembrance — it reminds me of the affective state that I succumb to when we celebrate Día de los Muertos. It was haunting and meant to invoke a sense of inhabitation of the moments that are familiar to Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, and other diasporic-adjacent people feel when in the throes of assimilation to the nation-state and its processes. You think about how all of these moments which are part of Cowboy Carter are Beyoncé, too — tragedies of family and relationships, the effects of devastation, exclusionary practices within society, racism, isolation, feelings of unbelonging, commercial success yet remaining along the periphery via awards and accolades, navigating a fragmented identity between “too much” of something vs. being “not enough” of it, and so on.

And I felt it most clearly when Parkwood Entertainment dropped beencountry.com.

It’s such a Beyoncé™ thing to do in releasing visual companions to her musical releases. And Bey has routinely “changed” the game in the musical industry because of initiatives she’s folded into her process of art making. The zeitgeist that followed Beyoncé (2013)4 altered how music is released — surprise drops were already a “thing” when it came out, had been paired with a visual companion album to each of the songs and shifted global drops to Friday. Lemonade in 2016 followed in the path of her self-titled but was a bodily experience to unique affective orientations that were inherently tied to Black womanhood. As a non-Black woman, I think there are emotional resonances within Lemonade that still stay with me, eight years later; it was a vulnerable expression to a journey of self-discovery, reconciliation, betrayal, and forging a dynamic relationship with our positionality and experiences amidst its overlapping, sociocultural and political texts and imagery. I’ll definitely never get over the release of “Formation,” its subsequent display at the Super Bowl, what living in the moment of Beyoncé fragmenting the notion of “having something to say,” while remaining “quiet” and embodying the realities of enduring, living, surviving, and learning to thrive amidst intergenerational trauma and the resiliency it takes to do it as a public figure.

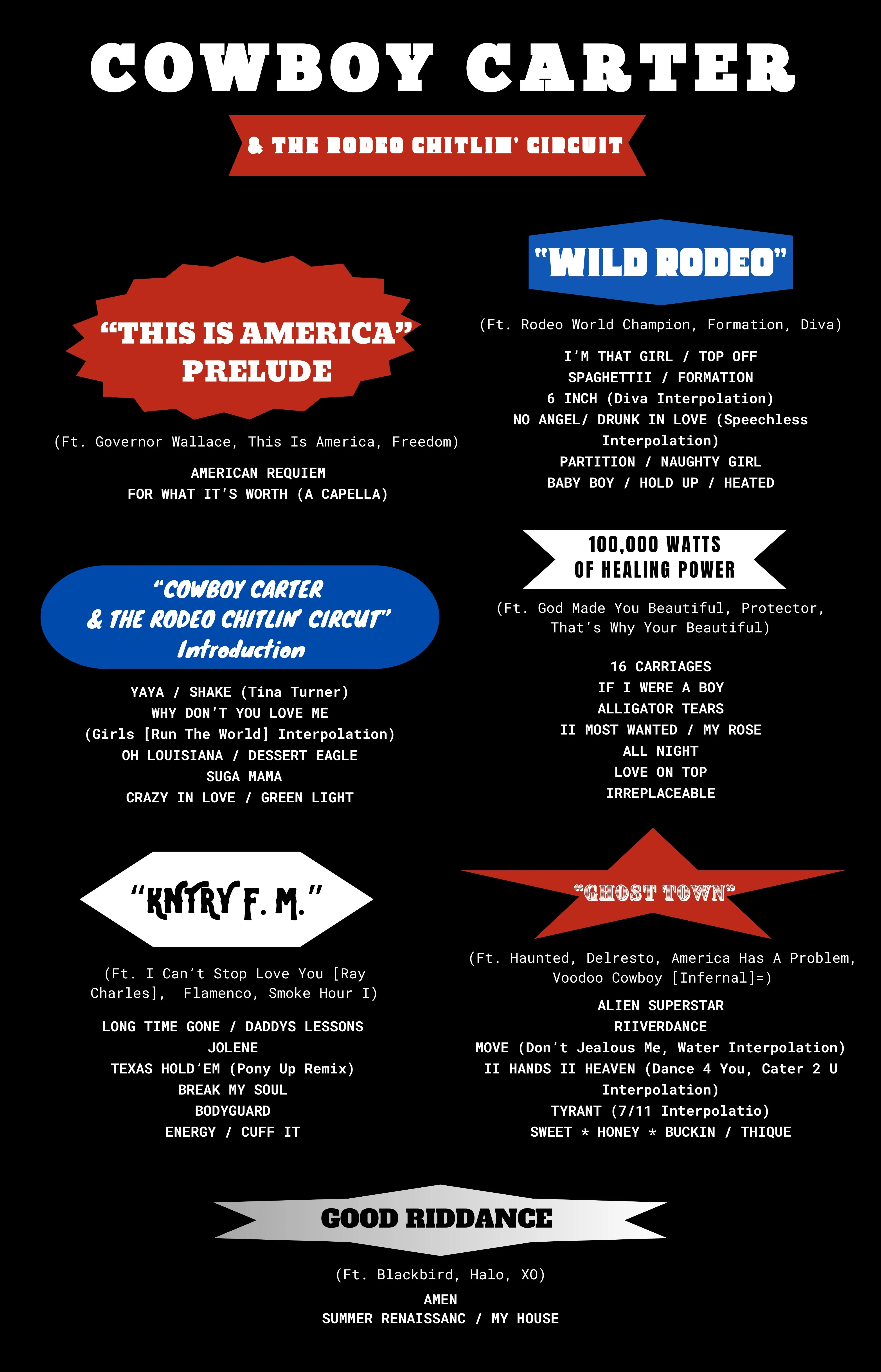

And I know that this moment is contentious for a lot of folks, but it isn’t about you and it certainly isn’t about me. I actually discussed this moment in my paper that I previously mentioned, as well as the logics built into that moment that are part of the Yoncé brand, but I’ll save it. With a discography that’s filled with back-to-back-to-back visual works, it’s really not surprising that fans anticipate an aestheticized journey to go along with the most recent album. Some fans speculate that Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé is the visual album to accompany its namesake, while others are convinced that the REAL visual work will emerge once Bey drops act iii (remember — Cowboy Carter is act ii, even though it was initially meant to be act i).

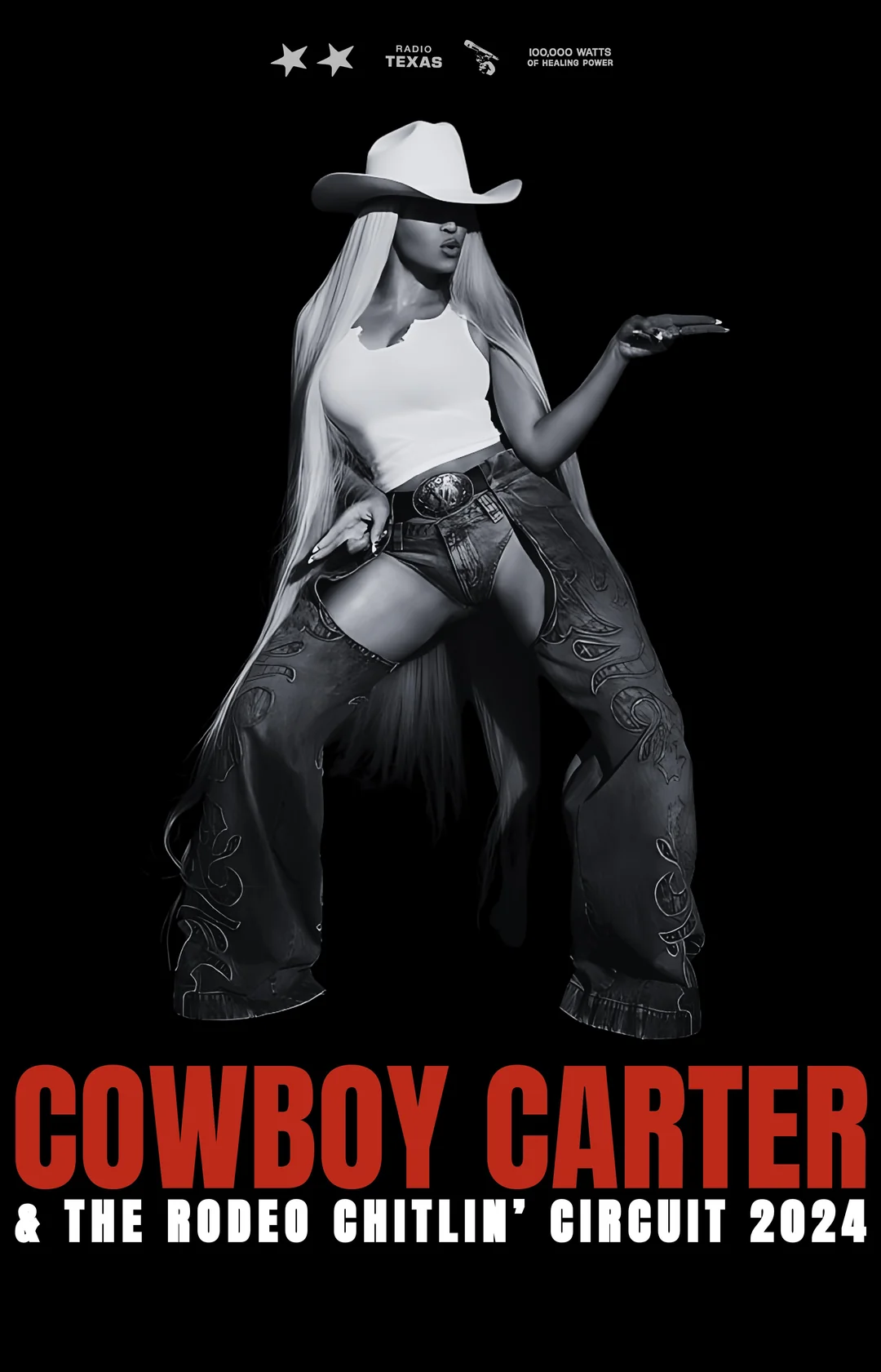

When beencountry.com dropped, I was SO ready. The website has had many definitions and went through several different stages of life in its two-month existence. The theories went wild – as is tradition for the Beyhive – and the purpose of the website was never actually outlined for fans… it was just there. Some thought that it would be the website to announce the Cowboy Carter & the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit World Tour and made some amazing images to fuel speculation. I’m quite glad that it wasn’t a tour announcement — I just sank money into new flooring for our home and I am fully prepared to break the bank to see Bey again (the closest I’ve gotten to the experience I felt at the Formation World Tour were but two: one, when I took my sister to see Lady Gaga on the Monster Ball Tour; two, when my husband agreed to tour our then-future, now home).

Fan made tour posters, April 19, 2024. Source: Reddit user TizzyTiz96.

I started seriously pondering the visuals of beencountry.com around late April, after the website had been updated for the eighth time. At this point, I wasn’t really asking questions of why she was using the website as a scrapbook or the significance of the assorted images during each update. I was thinking, “This is totally part of the ‘brand’ of Beyoncé.” It made me really step back and ask of what the process was here in thinking about the American West, the construction of the mythos that surrounds the images and scenery that pops up when we say ‘the American West’ or ‘the frontier,’ and the relationship that the American West has to the very idea of “country.”

It made me think about AMERIICAN REQUIEM when Beyoncé sings, “If that ain’t country, tell me what is?” and the way this echoed throughout the album and the trajectory of her career. It also made me think about the assemblage of photos and images that were put together on the website, and how these align with what we think we know about Beyoncé’s artistry and how much of that artistry and work she produces is disrupted by Beyoncé the performer, Beyoncé the businesswoman, but in particular Beyoncé the Black woman & Beyoncé the human being. All of these things overlap, and it was something I really wanted to think about further and work through. Is Beyoncé simply extracting cues of these cliched tropes and narratives of the American West, of country, that the intervention is offering us something potentially radical and new? For some people, the answer is “lol, no.” And that’s fine! We can look at the surface of her work, think back to “re-inserting absent communities of folk into dominant narratives” and call it a day. But I seriously think with how much dialogue and commotion that she causes to ignite — and remains steadfast quiet to allow for these conversations to take place — it’s such a disservice to the legacy of the art that she’s cultivating with the visuals she’s presently released.

My initial argument when I thought about beencountry.com and what Beyoncé was doing was guided by how her artistic decisions, innovative and interesting, have been converted into repetitive tropes that are no longer “brand new.” But that’s really what’s so interesting and complicated about Beyoncé… she creates a framework for us to think about her output in various manners, and we get to determine the kind of language that we want to use to understand and engage with the dilemmas that her artistry raises.

I’m thinking about what the images of beencountry.com illustrates, and what their short-term presence offers us in terms of a continued “afterlife” to Beyoncé’s visage. How much of an intimate look or impact do they make when we seriously think about the staying power they have? What does it mean to look at archival photographs — and when is the very moment that a photograph is turned into a historical document? When is this determination made, and who is qualified to make such an assertion? Does it necessarily matter whose authority we are challenging or refuting when we think about some disembodied “archive”?

I don’t know if I’ll get to a final point where I’m happy with my exploration of the website’s images (or if I’ll ever get through all of them). But I do know that I want to really sit with the works and process them. I believe that there’s something within the collected visuals on beencountry.com that linger and make me ask about the possibilities of exhausting them and what they might allude to. I think of Lisa Lowe’s writing in The Intimacies of Four Continents and her introduction regarding how we outline and define what “human” is, and what happens when we really take in the consideration that some bodies and individuals are excluded when this concept is interpreted and made concrete. For example, the human is predicated on its relationship with a non-human… what are the lasting effects of this conditional relationality? What happens when we seriously consider how the photographic works of beencountry.com as no longer antithetical to a historical archive that has operated on the exclusion of Blackness? How do we overcome the reality that nationalist forms continue to delineate and characterize who or what is “recognizable”? (Something which Indigenous scholarship also takes to task.)

As a side note, I really wish I could go back into my own history and tell little me how I would be seriously writing about all the things I was obsessed with as a kid. She would be shook! But maybe more excited that I was moving away from reading books to having the opportunity to be writing them. Girl power.

X., D

Notes

- I am quite happy to send a copy of the paper to anyone who asks. Given the rules of publication in the academic world, if any future publishers get a whiff of this paper being released anywhere on the web… it’ll never be a part of journals. 😦 Unfortunately, this is still a competitive, pay to play kind of world that I exist in. ↩︎

- Funny enough, in my writing I called her album “country-inflected” as an intentional choice to move away from some of the descriptive language that emerged out of Cowboy Carter. Some people said “country inspired” or “country adjacent” and even “country-like” which felt dishonest. This was an argument that follows the same trajectory that followed Lemonade‘s “Daddy Lessons” and was rehashed again when Lil Nas X released “Old Town Road.”

My reasoning is calling Cowboy Carter a country-inflected album was to avoid these descriptors, along with inspired, centric, styled, and influenced, because it was a mechanism to dissuade from producing a reading of the album as an interpretation that was derivative of those sound forms. By saying country-inflected instead, my belief is that I was reducing the inclination of seeing and perceiving Cowboy Carter as a “peripheral music album” that is being acknowledged only because it challenges the gatekeepers of “authenticity” to country music sound. Inflected simply means that the musical release curves, oscillates, bends, sways back and forth through ‘tropes’ of country music that are integral to, in, and throughout her album. ↩︎ - I still have plenty I could dig through when it comes to the centrality of the “mainstream Nashville” landscape with regards to country. Even knowing there is a continuation of outlaw country makes it less painful to acknowledge how prominent “bro country” is. ↩︎

- I certainly follow the line of thinking that Beyoncé’s self-titled really put the notion of a “visual album” on the cultural map, but we can’t deny that B’Day (2006) wasn’t a proto-visual album that carved a space for Beyoncé to flourish. ↩︎

Leave a comment